Originally published by Ink19 on June 11, 2025

Henry Fonda for President

directed by Alexander Horwath

An ominous and uniquely American thread connects the subjects of Mark Rappaport’s essays from 1992 and 1995 on actors Rock Hudson and Jean Seberg and the subject of film historian Alexander Horwath’s ambitious and affecting 185-minute debut feature, Henry Fonda for President. With its starting point in Midwestern small towns, this thread encircles the three screen legends and then extends into an immaterial plane of celebrity that challenges and distorts the distinction between the grounded person and the constructed image.

Both Hudson and Seberg, as evidenced through Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg, were — by their own symbiotic relationships with celebrity, which were fueled by their acting choices, romantic entanglements, and varying levels of political involvement from non-existent to aggressive — the victims of their crafted identities that eventually superseded any semblance of personal authenticity that is the trademark of the region they came from, leaving them a shell of their former grounded selves as their lives ended prematurely.

These essays now exist as grim biographies of these two actors and how their choices impacted them during socially repressive eras, but more importantly, they exemplify the Hollywood death loop of how celebrity emerges from our collective imagination, manifests into reality, and then reshapes our perception and expectations of said celebrity and ourselves. Though Henry Fonda, by comparison, managed to escape complete tragedy and destruction from this cycle, his survival reveals our nation’s insidious obsession with the concept of the “everyman” and our compulsive need to find it in public figures who are far from average in their work and lifestyles.

Serving as one of two narrators throughout Henry Fonda for President is the actor himself via an unearthed audiotaped interview with Fonda conducted over one week in his final year of life by Playboy magazine’s Lawrence Grobel which was recorded for a written piece to promote the actor’s autobiography, Fonda, My Life. Through carefully selected portions of the interview, we hear an aged Fonda in failing health recount multiple moments from his past. Touching upon everything from his Nebraska upbringing and theater experience to his famed collaborations with John Ford and aspects of his interpersonal connections with his celebrity peers, Fonda also directly addresses the foibles of his perceived public image as the “everyman” in American consciousness and his apathy towards the interpretations of his life filtered through his cinematic portrayals. Fonda’s narration is creatively juxtaposed against director Horwath’s narration as an Austrian-born cineaste who provides his outsider perspective on the actor who many viewed worldwide as the ultimate symbol of the “typical American.”

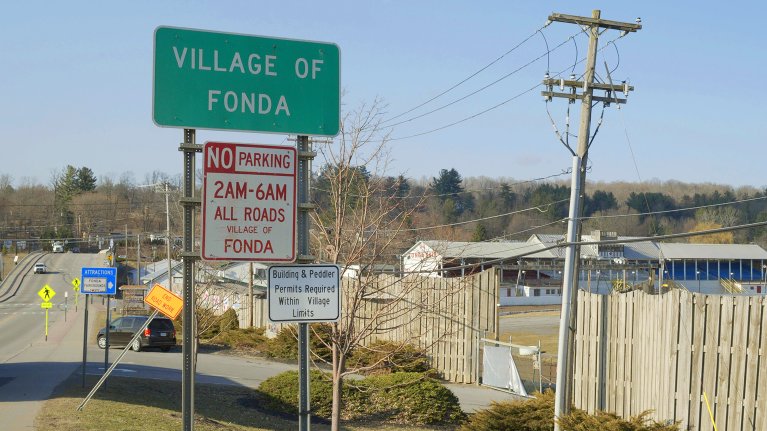

Beginning with a clip from a 1976 episode of the insufferable Normal Lear sitcom Maude where the titular Bea Arthur concocts a post-Nixon plot to run Henry Fonda for the highest office in the land, Horwath, along with editor Michael Palm, fashions the predominance of his piece in a similar way to Rappaport’s treatments on Hudson and Seberg: by adeptly affixing scenes from Fonda’s projects and films with moments from the actor’s life. But, Horvath expands the scale of his documentary by adding elements of contemporary footage shot at the original locations from Fonda’s most iconic films to weigh the myth-making power of Fonda’s oeuvre against the consequences of capitalism in the 20th century, which is the stronger force in reality today.

To this end, Horwath takes us to present day Tombstone, Arizona, the site of Fonda’s turn as legendary lawman Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine. A silver boom town that almost became a ghost town because of mining companies’ refusal to reinvest in critical water infrastructure after a fire, Tombstone is now a town reduced to a caricature of its frontier days, a cheesy tourist attraction where costumed actors play out gunfights for bemused tourists. As that moment transpires onscreen, Horwath surmises that the town only becomes revitalized by its notable past, a history that Fonda depicted and may have even diluted as evidenced by the shallow descendant representations of that same time in the present. More jarring stops are the still-operating migrant camps that Fonda’s Tom Joad rallied against over eighty years ago in the adaptation of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and the Old Trails Bridge that the Joad family crosses in the film, which is now owned by Pacific Gas & Electric, who are responsible for generations of environmental poisoning in the area. If Henry Fonda is the everyman in the American psyche, then these places that were the real sites portrayed in his films also have a role to play in the American collective mind, but, over time, both Fonda and the places become artifacts of what we as a nation opportunistically preserve or reject from our mythologies.

Seeing the creation and then dissolution of the Fonda myth through this visual technique of joining the filmic past with an inevitably dire present given our nation’s penchant for championing industry, expendability, and spectacle over quality of life, we begin to wonder to what extent Fonda himself attempted to control the cinematic perception of him as the socially conscious/left-leaning man. He reinforced this persona through his public affiliations with Democratic presidential candidates like Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy. And, he openly spoke about the roots of his social awareness, which he recounts in the audio interview narration in Horwath’s documentary: when he was fourteen years old, he observed from his father’s office the horrific hanging of Will Brown — a Black man wrongfully convicted of raping a white woman in Omaha in 1919. This event left Fonda feeling deeply outraged, and that outrage stayed with him throughout his life.

So, is it any surprise that throughout his career, Fonda was involved with multiple projects where innocent men are lynched or on trial? He assumed roles ranging from defender to executioner in John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln in 1939 to William Wellman’s The Ox-Bow Incident in 1943 to Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West in 1968, and most notably, played a conscientious juror in his iconic role in Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men. He had star power, but in the studio system of old Hollywood, you must always ask: how much autonomy did he have over the projection of Henry Fonda the everyman or the righteous liberal? Did he select the characters according to his own identity? Or was his mythical image carefully constructed for him? At what point did the image permeate Henry Fonda, the human? Horwath’s narration gives us a hint as we learn that John Ford, who directed Fonda in seven seminal films from Drums Along the Mohawk in 1939 to Mister Roberts in 1955, schooled Fonda on every aspect of his screen persona. From the way Fonda walked, talked, and even danced onscreen.

Yet, as Fonda’s career continued on, he would take on more roles as the elderly voice of reason, solidifying his position as the humanistic and astute moral core of cinema. Did he choose these roles — from sane presidents to compassionate fathers — in reaction to his real-life children, Peter and Jane, emerging as the vocal spokespersons for the radical Hollywood of the late 1960s? Was it essential to emphasize the myth more when Peter and Jane were both portrayed as being outside of Henry’s control, at least as seen by the media and public? Given that Henry’s home life was full of unexplained outbursts of rage, often towards himself, and a disturbing coldness towards those closest to him, which was noted by his multiple wives and children and was concerning enough that his second wife’s psychiatrist raised questions about his narcissistic tendencies, it makes sense that Fonda, at least in his later years, stated that he never saw himself in the parts he played. And, Horwath aptly connects these admissions to one of the actor’s films with a title that may be closest to his truth, My Name Is Nobody.

Regardless, Fonda’s audience was more than content with the relayed image. With the 1970s in full force, as the Maude episode implies, post-Nixon and post-Vietnam America was in desperate need of the homegrown, wholesome ideal epitomized by the nation’s perception of Henry Fonda. Shortly after the episode aired, the American public was granted its wish when it elected Jimmy Carter. Carter came into office with good intentions, but he was somewhat hobbled by his disastrous brother, Billy Carter, and was ultimately scorned for how he handled inflation and the Iran Hostage Crisis. And so, when Carter, the everyman, self-made leader, failed to heal the nation, America chose to embrace Fonda’s peer, actor Ronald Reagan, whose rally speeches even included lines from his own movies, most famously “win one for the Gipper,” from his portrayal of dying college football hero George Gipp in the film Knute Rockne, All-American.

It’s with the introduction of Reagan and his meteoric rise to power that Horwath’s film strengthens its thesis as the director draws a biting parallel between Reagan would-be assassin John Hinckley and his delusional obsession with Jodie Foster, which is cinematically mirrored by the Travis Bickle character in Taxi Driver who also aims to gun down a candidate for president. Here, we see Travis from Scorcese’s film with hair shaved into a pre-punk era Mohawk, which itself acts as an allusion to the Mohawk people displaced by the first Fondas who settled in the Mohawk Valley and to Fonda’s own role as Gil Martin, a fictional settler to the same area, in Drums Along the Mohawk. Reality begets image. Image begets reality. And, eventually, image begets image.

As with Rappaport’s essays on Rock Hudson and Jean Seberg, Henry Fonda for President is a deep dive into the biography of a legendary actor that works to effectively dissect the unique American fixation on the elevated celebrity whom we simultaneously hope is one of us. With Hudson, the onscreen epitome of the masculine movie star, the studios labored during his early career to hide his sexuality through arranged relationships until his AIDS diagnosis made his lifestyle public. Seberg, who outside of her well-publicised selection as Joan of Arc in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan and her role in Godard’s Breathless, remained a minor star, was ill-equipped to survive the onslaught when Feds plotted to end her career and destroy her public and private reputation after they discovered her affiliation with the Black Panthers. Henry Fonda — perhaps due to his ancestral heritage tracing back to the settlement of America or the less controversial nature of his flaws and sins or his blank canvas self that could easily morph and fit into the image created for and by him — lived and died in the eyes of the American public as the ultimate example of our aspirational decency and goodness, a fiction that we told ourselves throughout the 20th century, but did not live by.

Towards the end of Henry Fonda for President, Horwath takes us to Times Square where the images on digital billboards sell things we don’t need and a variety of street entertainers and caricatures capture the attention of tourists. The director follows a performer in a Donald Trump rubber mask, and we’re struck with the realization that the narrative of the everyman is still used today, but to more manipulative and perverse ends and by figures that are further from that myth than Henry Fonda, the actor, the symbol, and the man.

Henry Fonda for President

Photo courtesy of Mischief Films

Lily and Generoso Fierro