2015 was a transition year as Lily and I moved west, leaving behind some great friends, WMBR, and some of the best theaters in America. I send much love, thanks, and respect to all of the wonderful programmers out in Boston, to the many years that the blessed Harvard Film Archive in the basement of the Carpenter Center saw our shadows, to Saul Levine’s Film Society screenings that changed our view of experimental cinema forever, to the staff and films at the Coolidge Corner and the Brattle for always trying to make seeing a film a better experience, and extra respect to the small runs of films you would never see otherwise at The Museum of Fine Arts as well as all of the hard working and underpaid staff of the Independent Film Festival of Boston who put on another great festival this year, leaving no doubt as to what is the preeminent film festival in the city.

Since arriving in Los Angeles, we have been astounded by the amount of vital new and repertory cinema happening here. We are members of Cinefamily now, and through them, we have seen our favorite film of the year and met the director as well and have had the opportunity to view so many small indies and rep films that have long since been forgotten. The Cinefamily also supplied us with the best 4th of July that we can ever remember in the form of a barbeque, jazz combo, and a chance to see a print of Jazz On A Summer’s Day. We have loved our evenings at the majestic Egyptian and the Aero theatres as well. The small Music Hall and Fine Arts Theaters on Wilshire have shown films we would have missed if they had not picked them up, and all the goodly people at the American Film Institute put on a beautifully curated/free for everyone festival that helped populate this list. Films that we have waited for all year from world-class directors such as Arnaud Desplechin, Jacques Audiard, Cornelieu Porumbiou, and unfortunately Paolo Sorrentino, were on display at the Chinese Theater for one amazing week that will now be a part of every fall for Lily and myself.

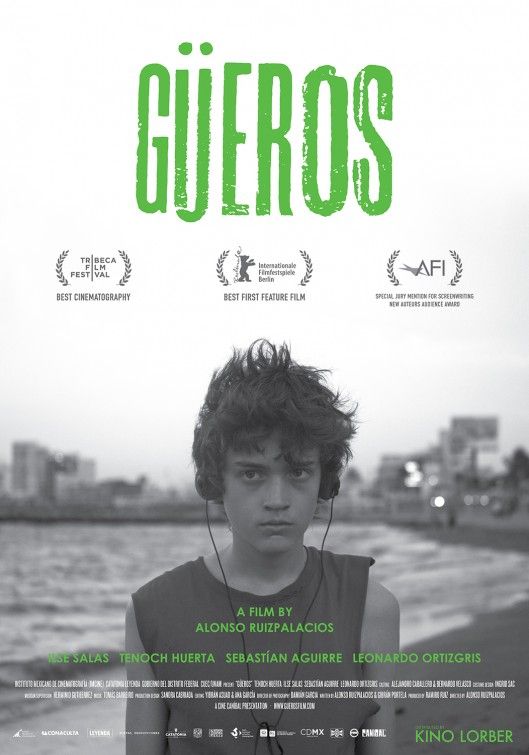

Of the 250 plus films we saw this year, some films went beyond expectations; a few from proven directors underwhelmed and disappointed, and our favorite film, Güeros, emerged as the winner, which is the the first time a debut effort has risen to the top in the twenty plus years that I have put out this list. Thanks to my darling Lily for watching these films with me throughout 2015 and for editing this massive document while graciously adding her fantastic thoughts in along the way.

Here we go….

My Top Ten Films for 2015

1) Güeros (Alonso Ruizpalacios) Mexico

Tomás (Sebastián Aguirre) is a teenage malcontent who lives in Veracruz with his mother. After pulling one nasty prank too many, mom sends Tomás to live with his layabout college student brother Federico/Sombra (Tenoch Huerta), who lives in a miserable apartment in Mexico City with another slack named Santos (Leonardo Ortizgris). Neither is actually in school because they are sitting out the “student strike” at their university caused by a change in policy that will now charge students for tuition for the first time in history. Shortly after arriving, Tomás tells his new roommates that his and Sombra’s favorite rock singer, Epigmeneo Cruz is dying in a hospital, and they have to see him before he goes, which is fine for the boys, since their large downstairs neighbor is about to kill them for stealing electricity. Set in 1999, their comedic voyage through the streets of Mexico City leads them to encounters with protests and freaks on their quest to find a rock hero, and all of the adventure is styled with sometimes funny and poignant nods to the pop culture and French New Wave style that serve to remind you of what we have lost since the 1960s. This film possesses a daring and rare combination of frenetic raw energy and a reverence of film history that I have not seen in many years, and it left me astonished. To say that this is an impressive film debut from Alonso Ruizpalacios is a massive understatement, and I cannot wait for his next film. All I ask is that you stay away from Hollywood Alonso, please. I’m sure you can do more good where you are away from the hipster starlets who descended on you after the Cinefamily screening because Güeros has far more than just denim, distressed tees, and navel-gazing politics and philosophy.

2) Dheepan (Jacques Audiard) France

Sivadhasan (Antonythasan Jesuthasan) is a Tamil Tiger soldier in Sri Lanka whose side has lost the civil war. To gain political asylum in France, he must have a convincing story, so he pretends to be Dheepan, the dead man of the passport he receives. In order to achieve the identity of Dheepan, Sivadhasan is also given a wife, Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan), and a 9-year-old daughter, Illayaal (Claudine Vinasithamby), to make his story more accurate and sympathetic to secure a visa. This new “family” goes through the motions of being a real family while Sivadhasan works as maintenance man for a housing project that is going through a gang war, making his desire to start anew and away from war pretty impossible. In some ways, Dheepan is a reversal of character of the small time hood to crimelord protagonist of Audiard’s magnificent 2009 film, The Prophet; Dheepan tries to veer away from crime and violence, which were integral to his past as a Tamil Tiger. Different in pace than Audiard’s other films, Dheepan is no less intense and heartfelt. What drives this film so high on my list is the naturalist performance from Antonythasan Jesuthasan, who himself was one of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and also used fake passports to escape to France. Kalieaswari Srinivasan equally shines as Yalini, who has less desire to remain in her new violent home. Dheepan was the surprise winner of the Palm D’Or at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival and deservedly so.

3) Right Now, Wrong Then (Sang-soo Hong) Korea

Directors Sang-soo Hong and Nuri Bilge Ceylan seem to genuinely appreciate how vile and brilliant they are as human beings. Their films consistently take their worst intentions to task with the difference being that Sang-soo has a lot of fun pointing out the more lascivious aspects of his persona. Utilizing the same Jungian structure as his previous two films, The Hill Of Freedom and The Day He Arrives, where the outcome of one’s life comes down to small decisions, the protagonist of Right Now, Wrong Then plays out alternative courses of a day on screen in different segments prompted by contrasting neurotic interactions. Right Now Wrong Then’s fill in for Hong’s alter ego is Han Chun-su (Jung Jae-young), an art house filmmaker who visits a small mountain town where he proceeds to spend the day trying to bed a beautiful but shy former model turned painter named Hee-jung (Kim Min-hee). The film is divided into two segments where Han uses opposite but similarly insincere techniques, one “self-effacing” and the other “brutally honest,” to get Hee-jung to love or at least sleep with him. Awkwardly painful in a way that a young Woody Allen would be proud of, Right Now, Wrong Then (which is actually reminiscent to Allen’s Melinda Melinda) is perfectly executed by the cast and Hong. You leave hating yourself for spending even one second hoping that Han and Hee-jung will hit it off, but you admire Hong for getting you to that point of recoil.

4) Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller) USA/Australia

I love George Miller, and he has never let me down (yes, I even like Happy Feet), but even my expectations were ridiculously high for this, the fourth installment of Mad Max, a series that helped define an era of post-apocalyptic films. I did start to worry though; it had been thirty years since Mel and Tina smashed around Thunderdome, and since then there were a couple of superb talking pig films, an entertaining adaptation of a witchy John Updike novel, and the aforementioned dancing penguin films, which all had me concerned that George had lost some lust for the fuelless ravaged wasteland. My concerns were somewhat quelled once I heard about the casting of Charlize Theron and Tom Hardy, two actors I have admired for years, and then, the first visuals finally convinced me that Mad Max: Fury Road was to be the big blow up film that I was not going to miss this year, and I am glad I didn’t. A brilliant decision by George to make Theron’s Imperator Furiosa the main character, relegating Hardy and virtually all of the men in the film as bystanders in the futuristic allegory that sees the passing of the male dominated film landscape through one hundred and twenty minutes of nonstop action. Maybe a bit more time with formulating some kind of dialog would’ve put this higher on the list, but all in all, this has too much explosive visual candy to not to roll around in over and over again.

5) The Assassin (Hou Hsiou Hsien) Taiwan/China

Sometime in the spring of 2000, The Museum Of Fine Arts in Boston ran a complete retrospective of Taiwan’s greatest living filmmaker, and I gladly watched all of his films to that point, ending with the period piece, Flowers of Shanghai. With each film, I grew in appreciation of his oeuvre; before the series started, I had only seen Hou’s Goodbye South Goodbye, and by the end, I saw the drastic transformation of his style. Over the last fifteen years Hou Hsiou Hsien’s work has concentrated more on contemporary settings and acknowledgments to key players in film history, as seen with his tribute to Ozu in 2003’s Cafe Lumiere. Hou has also relied on the talents of actress Qi Shu, who has starred in two of the director’s films since 2000, Three Times and Millennium Mambo, and now they have teamed up again in Hou’s first wuxia or historical martial-arts genre film, The Assassin. Needless to say that after thirty five years of directing dialog driven narrative film, Hou Hsiou Hsien was not going to direct anything that the genre has seen in the past. Qi plays Yinniang, who had been abducted by a nun as a child and has learned the martial arts of the convent to perfection and is now charged with killing her estranged cousin, a nobleman whom she was once promised to wed. Given the way that premise sounds, you may be thinking Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon here, but think again. Hou eschews a formal wuxia narrative and allows the visuals and mood to tell the story more than a tedious, clearly spelled out plot, leaving the viewer to draw all of their attention to Yinniang, whom Hou presents as a sympathetic but fierce protagonist who rivals Imperator Furiosa of Fury Road. With The Assassin, Hou Hsiou Hsien has created a sumptuously realized character study that proves that so much more can be done with the wuxia film than ever before.

6) Blind (Eskil Vogt) Norway

The second best debut film this year comes from the writer of the painfully underrated 2011 drama, Oslo, August 31st, Eskil Vogt. Blind features a phenomenal performance from actress Ellen Dorrit Petersen as Ingrid, who has recently been gone blind when we first meet her, and we spend much of the film inside of her head as the story unfolds. Ingrid lost her vision suddenly from an unknown condition and now spends her days at home and rarely leaves, even when she is accompanied by her husband, Morten (Henrik Rafaelsen), who works during the day as an architect. Vogt structures the film on the line between objective and subjective reality, as Ingrid believes that Morten sometimes heads home when he should be at work to spy on his wife, and maybe he is, but we are never sure if all of this is real or just Ingrid’s psychological projections. Blind triumphs due to Vogt’s ability to delicately balance comedy and tragedy as the film eventually becomes a bold statement about trust for people in love, and that never ceases to surprise the viewer.

7) The Duke Of Burgundy (Peter Strickland) England

Since his 2009 debut, Katalin Varga, English director Peter Strickland has been on a roll. In his last film, Strickland took the nebbishy Toby Jones to Italy to record foley splatters for giallos in the clever 2012 film, The Berberian Sound System. Strickland’s love of sound design comes to the forefront again early in The Duke Of Burgundy as does his affinity for the mid-1960s brown hues you would recognize from British fare like The Collector. The Duke Of Burgundy follows a housemaid named Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna) who is sexually subjugated by a butterfly scholar and collector named Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen). Is Cynthia actually in charge? We cannot be too sure based on the sexual role playing and alternating dominatrix play that occurs in their home. The Duke of Burgundy bears down on Evelyn and Cynthia’s idiosyncratic tendencies within their relationship and, in turn, what the pair is willing to do in order to maintain their myth of togetherness. This isn’t the worthless pap that is Fifty Shades Of Grey, which was essentially written to make middle American housewives rebel at their pathetic lifelong aversion of sexuality. Strickland expertly weaves two characters together who are constantly redefining themselves both intellectually and sexually through what they view as growth. Both Cynthia and Evelyn strive to distance themselves away from developing into domicile, “bedroom and kitchen” women, but through their feigned intellectual study and trite sexual endeavors in role playing, the two, especially Cynthia, travel closer to what they are trying so hard to run away from. The Duke Of Burgundy left me content with the thought that between Ben Wheatley, Joanna Hogg, and Peter Strickland, you can finally have some hope for a bright new wave of British filmmakers.

8) The Clouds Of Sils Maria (Olivier Assayas) France

Assayas has always been able to get amazing performances by his lead actresses: From Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep and Clean to Virginie Ledoyen in Late August Early September and Cold Water, Assayas writes beautifully for women and his actresses respond to the words. Such is the case with his latest film, The Clouds Of Sils Maria, where the brilliant Juliette Binoche plays Maria Enders, a veteran actress who learns that her mentor Wilhelm Melchior, a theater and film director, has passed away while she is en route to receive an award for him. When they hear of Melchoir’s death, Maria and her assistant Valentine (Kristen Stewart) were traveling to Wilhelm’s home in Sils Maria, an area in the Swiss Alps known for its haunting cloud formations and where the idea of eternal recurrence came to Nietzsche at “6,000 feet beyond man and time.” At the award ceremony, Maria is given the chance to star in a revival of Melchior’s play that made her famous twenty years earlier, but this time around, she will play the role of the older woman, turning over her original part as the older woman’s wily and tempestuous young lover to a rising Hollywood actress played by Chloë Grace Moretz, which forces Maria to ruminate about her career as an actress, her current friends and rivals, and her future. Much notoriety for this film exists because of Stewart as Valentine, who turns in an acceptable performance at best (giving Stewart a César for playing a one-dimensional uppity hipster is like giving Robert Blake an award for playing a psychotic ladykiller), but it is Stewart’s star power that allows Binoche more freedom with her role, and she takes complete advantage of that freedom to turn in another bravura performance in this contemplative character study.

9) Afirim! (Rude Jude) Romania, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France

Radu Jude’s 2015 film, Aferim!, a stunning depiction of early 19th century class and moral struggles, is not an exception to that Romanian film talent surge. Aferim! follows Costandin, a policeman, and his son, who have been hired by a boyar to find Carfin, a gypsy slave who has run away after having an affair with the boyar’s wife, Sultana. Teodor Corban plays Constandin with a grotesque and comical swagger as he doles out unsavory tidbits of wisdom to his son while debating the ethics of potentially releasing his captured gypsy slave, who he knows will suffer an atrocious fate when returned to his owner. Shot in gorgeous black-and-white but with an ugliness similar to a Sergio Corbucci Spaghetti Western, Aferim!’s story plays out in an uncompromising and illuminating way, provoking questions about Romanian history and how moral dilemmas are handled across time. With Aferim!, Radu Jude establishes a distinct perspective on the concept of a period piece, which offers great promise for his work in the future (it is believed that Jude will next adapt Max Blecher’s 1937 book Scarred Hearts).

10) Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands (Christian Braad Thomsen) Germany

It is amazing to me that director Christian Thomsen has been sitting on this footage of his friend, the prolific, and by all accounts, disturbingly fucked up German director, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, for this long. Thomsen fills Fassbinder: To Love Without Demands with archival footage and interviews with his friend beginning with their first encounter at the 1969 Berlinale, when Rainer was booed off of the stage for Love Is Colder Than Death, and closing with footage that Thomsen himself shot of an almost too drunk Fassbinder (even by his normal standard) just a few weeks before the untimely passing of the director of the acclaimed Ali: Fears Eats The Soul. Also in the mix is footage of Rainer flipping out on set and various interviews from a plethora of former actresses/lovers and collaborators who describe the director with a small amount of love and a whole lotta “whew, am I glad that he can’t hurt me anymore” looks. Though I am enjoying writing this review, Thomsen mostly eschews the sentimentality and platitudes while deftly glueing together the archival footage and interviews to create a clear profile of a furiously talented and tormented man, who despite his self-destructive tendencies, was also able to become one the finest directors of his generation. I must admit my own bias here that even if Thomsen had just showed his final interview with Fassbinder uncut, I probably would’ve appreciated that alone, but I am glad that the director added a calmer contemporary viewpoint to all of the madness that gives a more objective perspective on a man whose notoriety as a human has historically rivaled his career accomplishments in capturing the attention of the public.

SUPPLEMENTAL LIST

Catch Me Daddy (Daniel Wolfe) England

This nasty piece of UK filmmaking that seems to have been directed by Alan Clarke from beyond the grave is actually the debut film of music video director Daniel Wolfe and centers its narrative on the steady rise of “honour killings,” a trend that has gotten so out of hand in England that it now has an official memorial day for the victims of these crimes. “Honour killings” are acts committed to defend the supposed honour or reputation of a family and community. The crimes, usually aimed at Muslim women, can include emotional abuse, abduction, beatings and murder. Director Wolfe informs us of this crisis through Laila (Sameena Jabeen Ahmed), a British-Asian teen who has runaway from home with her caucasian boyfriend Aaron (Conor McCarron) to a trailer park in Yorkshire. Laila’s father wants her dead and hires two gangs to find her: one gang lead by a white Muslim-hating cocaine addict who is in it just for the fix and another by Laila’s brother. This will not end well and for two hours, Wolfe doesn’t let you off the ropes. This is ugly business without any sentiment, and like Clarke’s Made In Britain, which was made over thirty years ago, Catch Me Daddy hollows you out with its real-life inspired story of senseless intolerance.

Heaven Knows What (Ben and Joshua Safdie) USA

Though many compare this harrowing and impressive film from the Safdie brothers that follows a junkie named Harley and her band of fellow addicts on the streets of New York to Jerry Schatzberg’s 1971 feature, The Panic in Needle Park, to me, it more closely resembles a film that came out a year earlier than Schatzberg’s film, Barbara Loden’s Wanda. Though the protagonist of Loden’s film is not an addict, the titular Wanda, like the Safdie’s Harley, begins the film defiantly alone after leaving their significant other and soon becomes as desperate for connection to anyone while trying to survive. Both films feature naturalist performances from their leads who also wrote the story that they perform, with the notable exception that Arielle Holmes was actually a homeless heroin addict who lived many of the experiences that were transferred to her character. Arielle Holmes is the reason to watch Heaven Knows What as she tears you up as she falls again and again and her performance transcends the dialog during much of the narrative. I rarely add spoilers to my reviews but I applaud the Safdies for ending their film exactly the same way as the landmark film by Loden. It is a smart nod that reminds us that even after forty years, when the bottom falls out, it falls lower for the woman.

Dope (Rick Famuyiwa) USA

So, imagine if Superbad’s smart, nebbishy Evan was not a white suburban kid but instead a smart, nebbishy African-American kid from Compton. What would happen during those final days of high school if Evan messed up to the degree he did in Superbad but without being white and possessing middle class privilege? Well, whatever life-threatening disaster that you think would ensue happens to Dope’s protagonist, Malcolm (a star-making performance from Shameik Moore), a smart young man who dreams of Harvard and whose father left him with one thing before taking off, a VHS of Superfly that will come in handy once he becomes the guy who gets the bag from the guy at a bullet-ridden club party. Malcolm has only his brain and pulls from every source possible to gnaw his way out of the mess he has fallen into. Dope is somewhat of a mess and would’ve been on the top ten if not for the muddled middle third, but director Famuyiwa pulls it together in the end and makes it a fun watch that delivers a strong message for those outside of privilege who just want to get over. The soundtrack cannot boast a Curtis Mayfield track, but it does throw in some impressive early 1990s hip hop that locks in a man lost in his time for most of the film.

In The Shadow Of Women (Phillippe Garrel) France

2015 marks the 51st year of Philippe Garrel’s magnificent career as a director. Garrel has always prided himself on making deeply personal and economically budgeted films, and In the Shadow of Women follows his signature style. His best work since 2008’s Frontier of the Dawn, In the Shadow of Women is a story of Pierre and Manon, two down and out documentary filmmakers who are barely getting by but on the surface seem to care for each other greatly. Things begin to change when Pierre meets Elisabeth at the film conservatory and begins to have an affair with her. As Elisabeth’s love for Pierre grows stronger, a conflict arises as Pierre chooses to maintain his relationship with Manon, even though Manon may have eyes for another. This simple and comedic film is a bit of a departure from the usually intense Garrel relationship examination, but Clotilde Courau and Stanislas Merhar are wonderful as the emotionally confused leads, making this small, new film by Garrel a triumphant one.

MOST DISAPPOINTING FILM (TIED)

Youth (Paolo Sorrentino) Italy/USA

There had been some advanced press regarding the newest film by Paolo Sorrentino (The Great Beauty) as somewhat of a disappointment, but disappointment doesn’t even begin to describe the painfully overstated and poorly acted 2015 film by the Italian director, Youth. A clumsily executed allegory, Youth places veteran actors Michael Caine and Harvey Keitel in a Swiss resort where the young and the old (both of whom are quite haggard looking through Sorrentino’s overly elegant lens) strive to preserve their glory days while suppressing their worst memories and past acquaintances. With the success of The Great Beauty and the anticipated HBO series, The Young Pope, Sorrentino now has an American audience that he wants to continue to cultivate, and Youth is tailor-made to what he believes Americans want from an “Italian film.” As a result, it is a diluted, nearly insultingly dumbed down version of the style of his previous Italian films; Youth is a caricature of what Sorrentino believes the Oscar-following American audiences want, specifically those who herald films such as The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (which Sorrentino mentioned as an inspiration for commercial success during the Q&A). To add further injury, as made apparent in the post-screening conversation at AFI Fest between Caine and the director, Sorrentino does not have mastery of the English language, and this inability seems to have played a part in the facile dialog, especially between Michael Caine and his daughter in the film played by Rachel Weisz. Unlike his 2013’s The Great Beauty, Youth never fully grabs its central theme, leaving a morass of pandering images and dialog meant to impress rather than to complete a story.

The Club (Pablo Larraín) Chile

Second on our list of disappointments is The Club, Chilean director Pablo Larraín’s first feature film since completing his Pinochet trilogy with the highly acclaimed 2012 film, No. Having seen the predominance of Larraín’s work, it is clear that he is a bit of a hammer when it comes to making a political or social statement in his films. But whereas his earlier films, Tony Manero and Post Mortem, bring the level of symbolism to borderline surreal, The Club mires itself in a predictable story and thinly drawn up characters that cannot substantiate the severity of its best intentions to showcase the excesses and transgressions of the Roman Catholic Church. Much was made prior to the screening about Larraín’s choice to film with 40 year old Russian lenses similar to those used by Andrei Tarkovsky in Stalker, but unlike his choice of using early 1980s camcorders for No, which places you into the time period of that film set during the famed Pinochet “Yes/No” vote, the over diffused lens of The Club fails to enhance the mood or setting of the film, rendering it down to a trivial visual style detail. Alejandro Goic, who portrays Padre Ortega in The Club, explained after our screening that the film was shot in twelve days, and we’re sad to say it looks and feels that way.

WORST FILM OF THE YEAR

Goodnight Mommy (Severin Fiala, Veronika Franz) Austria

I love horror films; though I wouldn’t consider myself a fanatic by any means, I am always glad to hear about a new film from the genre that has piqued a friend’s interest. Unfortunately over the last few years, I have been besieged with not necessarily bad horror films but bland ones that have been presented to me as “game changers” that turn out to be the same tired premises in a new visual wrapper. Such was the case last year with the painfully bland Jennifer Kent film, The Babadook, which took its tired familial allegory into horror genre in an attempt to make it more interesting but ended up being neither frightening or innovative in any way. This year was David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows, which loses steam quickly despite its clever premise by betraying its own mythology and adding lame CGI effects where they weren’t necessary. Now that I have made my peace with the two films that I just mentioned, let me say that It Follows and The Babadook look like The Exorcist compared to the putrid slop that is this year’s overhyped horror film, Goodnight Mommy. Two worthless bratty, yuppie larvae who play with huge roaches in their pristine country home become suspicious that their recently surgically altered mommy, who has just returned home, is not actually their mommy. The boys hogtie their mom and proceed to torture her while Funny Games styled illusions of potential freedom for mom are danced in front of you to add tension or something like tension. Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz’s lame allegory here is that mom values appearance and status over her adorable yet subhuman children. Needless cruelty and creepy crawlies do not constitute horror nor do trite attempts to place pretentious vile crap like this into a sterile horror wrapper to sell to the States as high art.

BEST REPERTORY EXPERIENCE

Get Mean (Ferdinando Baldi) 1975 Italy/USA at Cinefamily

Shortly after arriving to Los Angeles and becoming members of Cinefamily, we had a blast attending a screening with cast included of a rarely seen spaghetti/time travel western from 1975 entitled Get Mean. Once Asian cinema began to overwhelm the action film landscape in the 1970s, the days of the spaghetti western were numbered, and thus the genre had to get crafty or else ride quickly into the sunset. To the rescue comes actor Tony Anthony, an American living in Italy at the time of Leone, who was well known for The Stranger character that first appeared in 1967’s A Dollar Between The Teeth. That film was successful, but Anthony was one of the first to see the writing on a wall in realizing that the genre needed some fresh ideas, so a year after that film debuted, Anthony and director Luigi Vanzi took The Stranger way east for The Silent Stranger (aka A Stranger In Japan), mixing the western with the samurai film. Tony wasn’t done yet with the Japanese sword epic, as he teamed up with veteran sword and sandal director Ferdinando Baldi and brought in ex-Beatle Ringo Starr to play the heavy for a spaghetti treatment of the blind swordsman, Zatoichi, in 1971 called Blindman, about you guessed it, a blind gunfighter. For years Blindman was next to impossible to get here in the States, and for that reason, it was pushed into cult film status alongside Anthony’s fourth entry into the Stranger series: a bizarre, genre-bending spaghetti from 1975 called Get Mean.

For Get Mean, Tony Anthony reunited with director Baldi and his co-star from Blindman, Lloyd Battista for this fantasy western where The Stranger, shortly after being dragged for a few miles by his dying horse past an ominous Phantasmesque silver orb, is offered fifty grand by a witch to escort a Princess back to Spain where she can regain her throne from the hundreds of Vikings and Moors who are battling it out back home. As bizarre as all of this sounds, Get Mean is an outrageously entertaining film which set up an even more entertaining Q&A between Anthony, Battista, and executive producer Ronald Schneider. They regaled the audience with bizarre stories from the making of the film that defied anything that I have ever heard coming from an independent production. There were also stories of weird financial transactions that kept Anthony on location while everyone else bailed in fear of retribution from investors and stories of close call money deliveries such a tale when twelve thousand dollars came just in time to feed Get Mean’s enormous cast before things “got ugly.” The outrageously charming cast stayed afterwards to sign posters and tell more stories to fans in the Silent Film Theater courtyard. Quite an evening.

A clip from the Get Mean Q&A at Cinefamily:

Original trailer for Get Mean