In recent memory, Amy Chua’s Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother was the last time I heard about the Asian-American experience in popular news. I’ll skip over my thoughts on the work because that demands an extended conversation for a different time and avenue, but with the high publicity of Chua’s work, Asian-Americans have an opportunity to begin to describe their experiences living within two somewhat contradictory cultures, and most importantly, to emerge as distinct voices (ideally, from my perspective, against the Amy Chua practices for breeding replicant, financially successful but soul and imagination empty Asian-Americans).

Released in the same year as Battle Hymn, Gene Luen Yang’s Level Up, tackled the Asian-American experience from the child’s rather than the parent’s perspective and aimed its message at children and young adults.

Before this review continues, I will make a specific distinction in describing the experiences of Yang’s and Chua’s work. In general Western media, they identify as works that discuss the Asian-American experience. However, as an Asian-American myself (who is culturally Vietnamese though genetically half-Chinese), I will say that the “Asian-American experience” is a far too broad of a term because the acculturation process in America greatly differs from culture to culture and nation to nation of origin. Consequently, I will take a stance and say that Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother and Level Up are specifically works that address the Chinese-American experience. With that moment of semantics over, let’s continue…

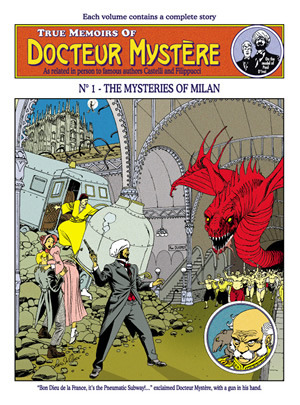

Cover for Level Up

In Level Up, Dennis Ouyang loves video games, but his destiny forbids him from pursuing his video game passion and gifts. Since early childhood, Dennis has received constant reminders that he must study and become a medical doctor, specifically a gastroenterologist, from his strict Chinese parents. Under the restrictions of his parents and their constant reminder that life is pain and full of sacrifices, Dennis succeeds in high school and stays on the course defined for him, but life changes when he encounters death for the first time; Dennis’s father dies of liver cancer right before he begins college.

To express his grief, Dennis devours video games, and in turn, shifts his priorities from academic success to beating video games, thus committing hours and hours to moving pixels rather than organic chemistry. As his destiny of medical school seems farther and farther away, a group of tiny angels appear in Dennis’s life, reminding him that he must become a doctor. With their constant urging and support on household tasks and studying, the little angels get Dennis back on track toward the day of his Hippocratic oath, and Dennis manages to go to medical school. Despite his academic success, Dennis has yet to answer the essential question: “What is my purpose in life?”

Thus, to no surprise, Dennis has a mental breakdown in his first year of medical school, realizing his decision to pursue a career as a gastroenterologist has no foundations in his own desires, only those of his parents. With this awakening, Dennis begins to introspectively question his motivations and slowly unravels his parents’ definition of his destiny to begin the journey of defining his own.

While I appreciated Yang’s ability to capture the guilt and the pressure to succeed in Chinese-American households and his own encouragement to young people to ask why one decides to pursue a career, I was greatly disappointed by the end of Level Up: Dennis, despite a brief hiatus from the doctor life as a competitive video gamer, returns to medical school, with the only new perspective to his career being that he will consider other medical specialties. After his brief introspection and his final understanding that this course to become a doctor existed because his father had failed to become one, Dennis does not really forge his own path; he defaults to the path he has always been told to follow, or, even worse, his father’s guilt in his own failure has become Dennis’s motivation to succeed as a doctor himself. Regardless of which reason is the one, neither sets Dennis up for a satisfied career as a doctor.

With Level Up, Yang had the great opportunity (and somewhat responsibility) to explore what success and ultimately happiness and confidence look like outside of Chinese-American standard expectations, but like Dennis the character, he chooses a safer route that does not completely rock the boat. Level Up could have been a work that encouraged young Chinese-Americans to explore their own interests and passions, but instead, it latently tells them that parent-defined expectations are the ultimate route we follow. Yang himself took his own life and career in a direction far from the Chinese preferred ones as a doctor, professor, or lawyer, and that thought process for his own life should have influenced the arc of Dennis Ouyang and made Level Up a far richer and far more revolutionary novel. But, alas, Dennis decides on becoming a doctor and even has some of his gaming interest filled with the game-like controller used in a Lower GI (oh, how, cute!).

To arrive at this happy doctor ending, Dennis does not ask himself if the medical material fundamentally interests him. He does not ask himself if the life of a doctor is what he really wants. He does not ask himself what other options exist to help people, which is the reason why he decides to return to medical school. He just decides that the gaming world is too trivial for him, and he selects the only other course he has ever known, preparing him for another crisis not too far down the road.

Level Up could have been a youth-oriented counterpoint to Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, but, sadly, it is somewhat of a complementary piece. I’ll have to keep waiting and hoping for that book from the Asian-American community that finally stands up and says no more to the Chinese-American standards of success. I just hope that it arrives before the onset of my own mid-life crisis.

Level Up, available by First Second, is written by Gene Luen Yang and illustrated by Thien Pham.