Upon returning to America from travels in Italy, it seemed wholly appropriate to pick up Sean Lewis and Ben Mackey’s Saints. As much as Generoso and I have been adjusting our diets as we re-acclimate with America, I figured that I should also readjust to American culture in comics by reading something mildly related to the Catholic churches and the gargantuan paintings we encountered last week. Also, at one point, we stood by the altar that contained Saint Peter’s remains, so Saints feels like a reasonable selection to reacquaint myself with the secular and non-secular blending that is embedded in the identity of America.

Lewis’s first foray into comics, Saints explores the intersection of reincarnation, sainthood, and the battle against evil. The spirits and the powers of Saint Lucy, Sebastian, Blaise, and Stephen have emerged in today’s world as adults who not only need to adjust to life but also have a divine calling to join together to battle a surge of evil. In biblical times, the archangel Michael defeated the devil and the fallen angels in the battle in heaven, but in our contemporary world, a man who claims to be the incarnation of Michael leads a society of congregations who offer their children to battle against saints, who are believed to bring about the end of times when they reappear on earth. With Michael’s increasing power, Lucy, Sebastian, Blaise, and Stephen begin receiving messages from God that lead them to each other in order to face Michael’s new children’s crusade.

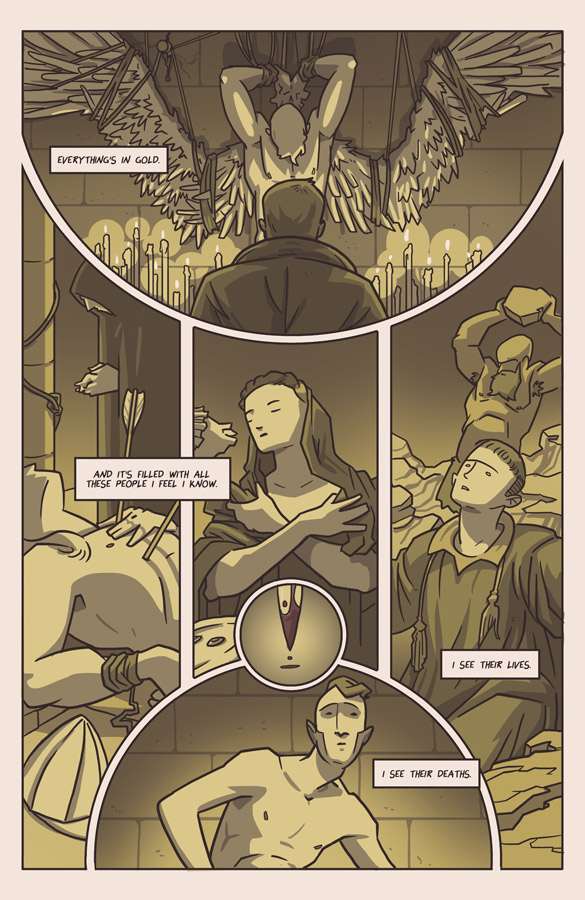

Favorite cover: Issue 5

Within a five issues, Saints packs in a ton. Lewis anchors the ensemble tale with the introspection and growth of Blaise, the saint with the least amount of confidence in his own identity much less his responsibilities to God and humanity. In secular reality, Blaise has attached himself to failed metal groups in order to relate to other people, but his connection to the metal groups feels all too thin and full of false idols. Consequently, when Blaise begins having recurring cryptic dreams set entirely in gold with strangers he feels some familiarity with, he does not dismiss them, but he also does not attempt to understand them. That is, until Sebastian, one of the people in the dream appears at a concert and explains that Blaise’s dreams signify a higher calling.

Once Sebastian and Blaise find Lucy and Stephen, the group attempts to decode why they have received messages to come together as well as their history in their previous lives. When the modern Michael’s army begins to attack them, the group goes into hiding and spend more time trying to understand each other, making Saints less of a superhero tale about the battle between good and evil and more of a road tale, where traveling forces characters to better understand their purpose.

Saints has a fascinating premise, and I must admit it kept me engaged even though the execution of the storytelling may not be the best. In an interview, Lewis described the writing process as one where he wrote a short story that he and Mackey then dissected to form the panels. This distillation from a longer story rather than the construction of a script or storyboard leads the first couple of issues of Saints to have a clumsiness and awkwardness in the progression of ideas and conversations from panel to panel and page to page, but by the fourth issue, the bumps begin to smooth out. Mackey’s shifts in color help ease the transitions from dream sequences to the saints’ reality to the building of Michael’s congregation and army, so even though the panel flow does not always work in the first three issues, you never get lost between the different branches of the story.

Given its non-secular focus, I cannot bypass a discussion of the adaptation of biblical concepts. I, in no way, am a scholar of Christianity, but I do understand some of the core tenants of the Bible. Lewis definitely loosely interprets the archangel Michael, but his modernization of the saints does not feel too distant from their original personas. While a secular fictional tale about the faith could use saints’ powers as superpowers, I appreciate that Lewis de-emphasizes the saints’ supernatural abilities and focuses the series on the saints understanding their divine calling; I hope Saints begins to focus more on the psychological aspect of the martyrdom of these saints, for those ruminations could make this series rise from just being entertaining to something daring and innovative. Additionally, the martyrdom aspect of the saints distinguishes these characters from any others out there in the comic book world that have some supernatural ability and some responsibility to other humans; by exploring this security or insecurity in faith and grace or hesitation toward martyrdom, Saints can emerge as a faith based series that intelligently and relatably discusses how to interpret and apply faith in a modern world.

Saints has solid footing in an excellent concept. I hope it digs further into the hearts and minds of its characters and their conflicts with their higher calling, but regardless, I’ll still follow along because Lewis and Mackey are aiming for a big idea and have yet to enter the pretentious territory, and that impresses me.

Saints is written by Sean Lewis and illustrated by Ben Mackey. Issues 1-5 are available via Image Comics.