The concert film, that relic of the screen before MTV, is still kicking around in 2015, though an artist has to reach the level of international fame of a Katy Perry or Justin Bieber before producers are willing to bankroll a two hour ego extravaganza to be seen by screaming teeny boppers worldwide. Prior the dawn of MTV, the concert film was the only way for many small town folks throughout USA and the globe to see a range of world class acts who wouldn’t come to their town in a larger than life way. As a boy I loved staying up late to watch Don Kirschner’s Rock Concert, the syndicated weekly live music show that brought many of us our first glimpse at rock and soul acts from Curtis Mayfield to Cheap Trick, but there was nothing like going to a theater to see a twenty foot tall Mick Jagger strut his stuff. In these years prior to the insanely expensive fees that now exist for music licensing, the concert film of the 1970s was a low risk moneymaker.

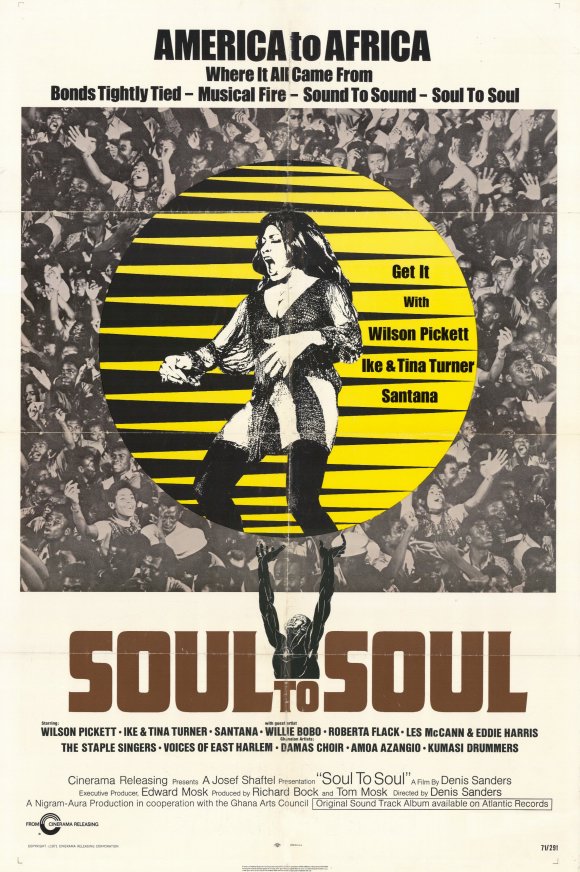

Adding into the frenzy of rock concert films was the wake left by the popularity of Gordon Park’s 1971 blaxploitation crime drama “Shaft” and its Academy Award winning soundtrack by Issac Hayes. Finally, Hollywood was now not only looking to distribute Afro American narrative films but also documentary films celebrating soul music that had the added potential of releasing a high selling soundtrack. Columbia distributed “Wattstax,” a 1973 concert film depicting the Stax Label fueled musical event that commemorated the Watts riots of 1965, and “Save The Children,” the film of the star-studded show attached to 1972 Jesse Jackson-led PUSH exposition held in Chicago, which was distributed by Paramount Pictures. Hot on the heels of “Shaft” and before even “Wattstax” and “Save The Children” was Denis Sanders’ superb documentary on the fourteen-hour concert that took place in Accra, Ghana in 1971, “Soul To Soul.”

After declaring its independence from England in 1957, Ghana had attempted to connect with a multitude of African diasporas and succeeded by getting the attention of poet Maya Angelou, who reached out to Ghana’s Prime Minister, Kwame Nkrumah, to invite many Afro American musicians to Ghana to help the newly independent country celebrate its freedom. Many years later, after Nkrumah was deposed, producers Tom and Ed Mosk presented the same idea to the Ghana Arts Council who agreed that the time was right for such an event to happen and thus the Soul To Soul concert was born. Amongst the American artists who would perform were some immensely popular soul artists: The Staple Singers, Ike and Tina Turner, Roberta Flack, and Wilson Pickett. The San Francisco rock group Santana would join the bill as would jazz performers Les McCann and Eddie Harris. Many Ghanian artists such as Kwa Mensah, The Kumasi Drummers, Charlotte Dada, and even house band for the Ghana Arts Council, The Anansekromian Zounds would play their hearts out for the tens of thousands in attendance.

The narrative construction of “Soul To Soul” would be much different from the previous mentioned “Wattstax” and “Save The Children” as far as showing the political (read: non musical) environment surrounding the concert. Gone are the moments within the town to hear what non-musicians think about the day-to-day lives. The few interviews that do exist in this documentary are mostly relegated to the beginning of the film, when the planeload of traveling soul artists is asked about their expectations for performing in Ghana. The musicians speak with great enthusiasm on their feelings about going back to the motherland, the clothes they will find and the people they will meet, but they all seem rather underwhelmed by the potential of hearing great music while there. Once they all land in Ghana, the wide-eyed tourist in our American envoy quickly disappears, as once they hear what their fellow musicians from Ghana can bring to the table, it becomes all about the music from that moment onward. A wide-eyed Tina Turner learning how to sing from a powerful Ghanian vocalist in the street is a moment that sums up the early collaborations well.

We then see the live concert, expertly filmed with brilliant sound that surpasses many films of its kind from that era. On stage, Ghanian musicians playing solo or with some of the American acts add a powerful communal element to the show. Also not lost on this viewer are the looks of awe from the audience upon seeing Tina and her backup singers howling out notes and gyrating wildly during “River Deep-Mountain High” in a way that I am sure would be scandalous for musical performances by women in Ghana at that time. Some dance in the crowd, but many just stare with open mouths and confused stares. More subdued but no less awe inspiring is the performance of Curtis Mayfield/Donny Hathaway written soul stirrer; “Gone Away” that Roberta Flack heartbreakingly sings that almost silences the enormous crowd. Strangely, Santana performs the most African sounding music of any of the American artists much to the crowd’s delight. The Staple Singers are given a few numbers on film and in general perform even better than they did on “Wattstax,” especially Mavis Staples on lead vocals, and the great Wilson Pickett, an audience favorite, gives his all as he always does.

There many powerful moments woven in between the live concert scenes, including a wedding and a funeral ritual that are seen without any over narration, and a trip to one of the many “slave castles” in Ghana that is done with few words from the guide and with a very poignant rendition of “Free” sung in acapella in the background. These scenes feel organic due to their placement, and therefore, flow well within the film’s construction as opposed to the attempts at similar emotional moments that are dispersed haphazardly in “Save The Children,” which leave you cold.

Original 1971 Trailer For Soul To Soul

Sadly, “Soul To Soul” saw less distribution than needed during its initial run, and the Mosks did not make back their initial investment, so the documentary was near impossible to locate for many years. Thankfully, The Grammy Foundation paid for a restoration of the film and reissued it back in 2005 with added footage, interviews, and a companion soundtrack that I’m sure would’ve been a must-have had the film be seen by more of an audience back in the day.