Originally published on Ink19 on December 13, 2024

In a year where chaos continued to reign supreme, our favorite films naturally do not have a consistent thread running through them. Instead, there are patterns that convene in our best of film selections that may not logically fit together, but alas, feel like an accurate collage of the ideas, images, sounds, and texts that reverberated in our minds this year.

For the first time, we have four films from Canadian directors that represent three provinces on our list, with each film capturing key essences of its portrayed region. We also have three films that meditate on the concept of the spiritual quest. There are two challenges to the biopic form, two Argentinian re-interpretations of the crime genre, and two works from French cinema stalwarts that cultivate all of their fascinations and their methods into supreme culminations. In addition, there are three documentaries that use repetition in thought-provoking and revelatory ways.

Despite these many differing motifs, there’s one commonality, perhaps obvious, in our selections for 2024 that we should articulate. All of these films are specific: to a geography, to a zeitgeist, to an experience, to a technique. This may seem like a prerequisite for any respectable piece of art, but as the forces of cultural homogenization become more dominant via algorithms every day, never has specificity been more necessary and critical.

As with every year, we’d like to give our appreciation to the outstanding folks behind Acropolis Cinema, AFI Fest, Independent Film Festival Boston, the Brattle Theater, Films at Lincoln Center, the Coolidge Corner Theater, and the Cleveland Cinematheque for their programming and their unwavering efforts to preserve the communal experience and audiovisual wonder of filmgoing. Please support these festivals, microcinemas, and independent theaters in their substantial work.

• •

Việt and Nam / Philippines, France, Singapore, Italy, Germany, Vietnam / dir. Trương Minh Quý

With each of Trương Minh Quý’s films, the director sets forth ideas of the cosmic and the historic along with the multi-layered conceptions of house and home and allows us to watch all of these forces clash and interplay. In his most recent feature, Việt and Nam, Trương’s method has reached its highest form to date, resulting in a hypnotic, moving film made up of various interwoven, open-ended essays on Vietnamese culture and history, all of which are framed by the relationship between the two titular characters. The plot of Việt and Nam is simple albeit particular: Việt and Nam are miners who are best friends and lovers. In the year 2001, Nam is getting ready to leave Vietnam in search of a better future outside of the country, and the film documents the period where Nam looks towards his unknown future and bids his farewell to a present that will soon become the past. As such, history and collective memories weigh heavily on each of Nam’s interactions with his surroundings — his home, his workplace in the mine, and the forest where he attempts to help his mother recover the remains of his father who was killed in the Vietnam War — and his relationships with his mother and Việt, imbuing Việt and Nam with a profoundly elegiac tone. Haunted by the real future incident of the discovery of thirty-nine Vietnamese migrants who were killed in a lorry container that landed in the UK in 2019, Việt and Nam intimates a tragic end to Nam’s departure, but remains fixed throughout on all of the forces that encourage Nam’s migration. Trương offers a multitude of ways that fixations on the past extinguish potential, swelling up Việt and Nam into a mourning cry for the loss of home for all who departed Vietnam’s shores and the loss of opportunities and vibrancy for a country that lost its people. Misinterpreted as a work of slow cinema in the manner of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Việt and Nam is, in fact, a collage of cinematic techniques ranging from long-takes to cross-cuts, which build the momentum of the film to take us from the bowels of the Earth to its surface and then to a plane above. We had the honor of speaking with Trương Minh Quý in the days before Việt and Nam screened at AFI Fest 2024. You can read that conversation here.

• •

New Dawn Fades (Yeni șafak solarken) / Turkey, Italy / dir. Gürcan Keltek

Symbols and signs have never been more important, and less recognized, than they are today. We are constantly bombarded with visual stimuli as our experiences of reality are mediated by a variety of screens on phones, laptops, televisions, etc. In order to make it through the day without a complete cognitive meltdown, we rarely stop to try to decipher each image and word and deduce what is being signified, and we certainly are remiss in paying such close attention to the objects in our physical reality too. Gürcan Keltek’s superb fiction debut, New Dawn Fades, valiantly takes up the task of revitalizing the significance of sign theory in experience. The film opens in the Hagia Sophia, panning the walls covered in writing and the geometric ceilings of the iconic place of worship, and then narrows its view on Akın (Cem Yiğit Üzümoğlu), our physical and mental guide through Istanbul’s present and unseen past. As we look at Akın in the mosque (and former church), we hear unintelligible, multilayered whispers: the tourists in the background are speaking, but voices from the past or from within Akın are present too. He then returns home to his mother, where we learn that he has recently completed a period of institutionalization. He is clearly still not well, but his mother worsens the situation by relying on medieval beliefs and practices to try to release the malevolent spirits plaguing her son. As such, home is not a place of convalescence and restoration for Akın, and he takes to wandering Istanbul, visiting people and places of varying degrees of significance to him as ancient, Byzantine, Ottoman, and contemporary forces infuse into his perception. Keltek allows us to experience everything as Akın does, and the sound design by Son of Philip acts as a non-verbal representation of Akın’s sign processing, which steadily builds towards a messianic vision (or delusion). Akın’s mental response to the symbols that he encounters may not be fully understandable by those of sound mind, but his ability to detect such signs remind us of how powerful they can be and how our decisions to avoid interpreting them may be paradoxically protective and destructive. We wrote a full review of New Dawn Fades during its festival run this year. That piece is available here.

• •

Tardes de soledad (Afternoons of Solitude) / Spain / dir. Albert Serra

In many of Albert Serra’s films, the frame is the theater stage with a pedestal, and on it is some figure(s) of grand stature, by way of history, notoriousness, and/or national standing, whom the director will strip down and reduce to their most basic form for all of us to examine away from any facades that once entranced us. This Serra method is in full effect in his latest film, Afternoons of Solitude, a documentary which meticulously captures the in-arena trials and tribulations of the world’s leading torero, Andrés Roca Rey. There’s little glory to be had or found in Serra’s rendering of Spain’s controversial, but nevertheless significant national pastime: the director presents close-up studies of multiple corridas without any shot of audience reactions, and though the fights are stitched together by a handful of beyond the arena scenes of transit, undressing, and dressing, the bullfights develop into an increasingly predictable loop, with each fight differentiated merely by the change in costumes by Rey and his cuadrilla and, of course, by the change in the bull opponent. Like a three-act play, a bullfight is structured in thirds, and its script plays out as consistently as that of a passion play. Occasionally, the fight veers off course: a bull attacks and nearly steps on Rey in one and pins him to the arena wall in another, but the script corrects itself each time, with the cuadrilla stepping in to help, Rey returning to the battle full of bravado, and voices exclaiming admiration for Rey’s manhood heard over the images of the torero continuing on until the bull is killed and dragged away by horses, leaving a large streak of blood in the arena sand. Even though we see the arcs of the bullfight over and over again, Serra’s documentation of this national play/shared ritual never becomes tedious thanks to the incredible close-ups and dynamic editing that draws our eyes to the faces and the natural materials and fluids as well as the man-made substances and objects that are essential to a bullfight. The horror of the violence repeatedly enacted towards the bulls in the arena does not go away, but our emotional activation dampens with each fight, replaced by a new lucidity: bullfighting is a tradition that feeds the spectator’s primeval motivations and tendencies at the cost of animal and human life. Afternoons of Solitude dissolves our collective consciousness’s fascination with bullfighting and confronts the culpability of the viewers of the sport. It could become one of the most important records of a long extinct pastime some day in the future — if only we could step away from our deeply rooted attachment to violence.

• •

Comme le feu (Who by Fire) / Canada, France / dir. Philippe Lesage

One of the most energetic reflexive works about filmmaking that we’ve seen in many years, Philippe Lesage’s Who By Fire lures us into a spider web overseen by Blake Cadieux (Arieh Worthalter), a once famous fiction filmmaker who has moved on to become a documentarian and a woodsman (of sorts). Blake invites his former screenwriting partner, Albert Gary (Paul Ahmarani), for a retreat and reunion at his palatial cabin in the woods, and Albert brings along his college-aged children, his daughter, Aliocha (Aurélia Arandi-Longpré), and his son, Max (Antoine Marchand-Gagnon). And Max brings along his best friend, Jeff (Noah Parker), an aspiring filmmaker. When Albert and company arrive to the cabin by a seaplane flown by Blake himself, they meet Blake’s editor, Millie (Sophie Desmarais), his best friend and assistant/wilderness guide, Barney (Carlo Harrietha), and the house chef, Ferran (Guillaume Laurin). At this point, nearly all of the crew members needed to make a film are present, and Blake naturally takes on his role as the director as well as the lead actor in the group’s dynamic even though the cameras aren’t rolling. Blake’s command at the dinner table the first night raises old tensions between him and Albert, and this clash between the former collaborators lets loose an uneasiness that permeates the film. Despite the dominance of Blake as a character, Lesage anchors Who By Fire on Jeff, and as the film progresses, we see the awkward and highly sensitive Jeff get caught between his attraction to Aliocha and his eagerness to impress and learn from Blake, who is quick to share his director’s copy of the screenplay for one of his most famous films with his aspiring disciple. Much to his embarrassment, Jeff gets lost in the woods at night after making a confusing pass at Aliocha and has to be rescued by Blake the next morning. Then, in the late hours of the same day, Jeff catches Blake and Aloicha together as his would-be mentor takes partially clothed photos of his object of desire. Jeff seethes, but he can do little in this space where all activities, including lounging, fishing, dining, or canoeing, are set up and helmed by Blake. As a result, Who By Fire materializes a microcosm where artistic striving crashes into grappling between generations, the older clutching onto what remains of its dominance and the younger trying to ascend while also desperate to glean knowledge and wisdom from its contender. And yet, the film is also an ode to filmmaking: a celebration of the joy, dread, drama, and sadness that the moving image can bring because Blake takes Jeff and all of the people in the cabin through each of these emotions with different situations masterfully constructed and integrated together by Lesage and effortlessly lensed by cinematographer Balthazar Lab. In turn, Who By Fire rejoices the possibilities of cinema as an artform while also sharply articulating the limitations to its progression that people, be it themselves or others, place on it.

• •

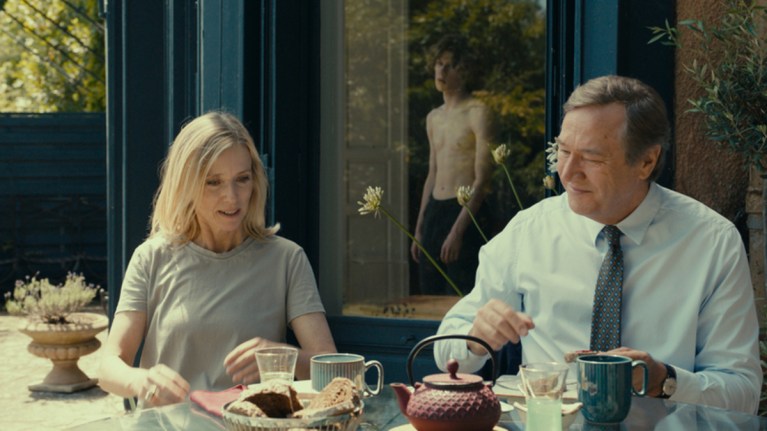

L’Été dernier (Last Summer) / France, Norway / dir. Catherine Breillat

There’s something amazing about Last Summer even though its premise around an illicit affair between a stepmother and her stepson is straightforward and its execution doesn’t immediately appear to challenge any conventions of cinema on an initial viewing. But, after some contemplation, what readily becomes apparent about Last Summer is its effortlessness in its unraveling of female desire in an extremely inappropriate relationship, a topic that has dominated the works of Catherine Breillat for decades. With Last Summer, all of Breillat’s daring provocations and examinations of female desire are elegantly channeled into the relationships, self-image construction, and traumas of Anne (Léa Drucker), a prominent attorney who protects abused minors. Anne has a seemingly enviable life: she is well-respected in her career and lives in splendor with a successful and loving businessman husband, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), and two adorable adopted Asian daughters on a modest estate protected from the outside world and nearby Paris by lush foliage and beautiful lawns. But, in a moment of intimacy between Anne and Pierre, we see fissures in Anne’s picture perfect existence that hint at a traumatic early sexual experience, and upon the arrival of her stepson, Théo (Samuel Kircher), the fissures begin to rupture, propelled by an entangled mess of Anne’s first sexual encounter, the repression of her sexuality overall due to the AIDS pandemic during her early adult years, a fatalistic desire to demolish the life she’s created for herself, and her attraction to Théo’s beauty, sensuality, and rebellious energy. All of these are heavy forces that compel Anne to continue her relationship with Théo, but Breillat expertly infuses them into glances, conversations, and, of course, sexual acts such that nothing ever feels like an overt proclamation or explanation of motivations. As a result, such nuances extend Anne’s character naturally in a highly unnatural, objectionable situation to the point where our judgment of Anne is overtaken by a lucid understanding of her actions. We all know Anne’s relationship with Théo is wrong, but the reasons for its existence and endurance are fundamentally human and, though complicated, within the realm of reasonable comprehension. Last Summer feels like a film that only a later stage of Catherine Breillat could make: there’s no viscera or physical brutality here, only the psychological tumult brought on by the self and others as well as by societal and familial forces — a kind of violence that permeates our own thoughts and desires even if our consequent actions are radically divergent from Anne’s. We reviewed Last Summer during its US theatrical release. You can read our full piece here.

• •

C’est pas moi (It’s Not Me) / France / dir. Leos Carax

Before we dig into It’s Not Me, we do feel the need to address the “what” of Leos Carax in output and opinion prior to this point in his career…Carax was only 24 in 1984 when his celebrated debut feature, Boy Meets Girl, was released. Universal acclaim for his triumphant follow-up, Mauvais Sang (Bad Blood), exalted him as the next great young voice in French cinema, a title that was virtually stripped away after his third feature Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (The Lovers on the Bridge) went spectacularly over-budget and polarized critics, which led him to respond with Pola X, his fittingly bitter adaptation of Herman Melville’s critically detested novel, Pierre: or, The Ambiguities. After the death of his longtime collaborator, cinematographer Jean-Yves Escoffier in 2003, it would be nine more years before Carax’s Holy Motors would hit theaters, a luxuriously enigmatic masterwork that simultaneously honored and challenged cinematic conventions — a film that also subsequently landed on multiple best of the decade lists, including ours. Now, at 64, with his long desired Sparks musical Annette directed and behind him, Carax has internalised the loss of Jean-Luc Godard and connects JLG’s later compositional filter to his own œuvre and historical and contemporary worldview to compose It’s Not Me, a commissioned short film for The Centre Pompidou, a video essay response to the question posed by them: “Who Are You, Leos Carax?” Visually stunning and enthusiastically chaotic in presentation, Carax pulls together the pieces that vacillate wildly inside his mind, from the films seared into him from his own filmography to Murnau’s Sunrise and Hitchcock’s Vertigo to stark documentary footage of Nazi rallies, dictators galore, and drowned migrant children. Carax connects the stimuli to his psyche and supplies his own over-narration, which at times is as judgemental of others as it is self-effacing, and even occasionally lovely with sequences dedicated to the people closest to him, his daughter and Jean-Yves Escoffier. For those uninitiated to and less appreciative of all things Carax, It’s Not Me, will most likely not have the same kind of impact as other directors’ introspection pieces like Bertrand Tavernier’s My Journey Through French Cinema or Varda by Agnès, as those delightful films strive more for a display of personal influences and experiences than what Carax clearly intended for his short: an admission that he still actively searching history and himself for answers to the whys of the world and the present state and potential future of his beloved medium. Though Carax’s undertaking may seem a bit overwhelming to address in a scant forty minutes, It’s Not Me’s overall power lies less in any answer given, but in its glittering omnibus of ideas that come together as questions. Lastly, we must thank Leos for giving us the most surprising and exhilarating post-credit sequence in film history!

• •

Matt and Mara / Canada / dir. Kazik Radwanski

A comedy of manners about the reunion of two estranged friends who are writers living in a rarefied air, Matt and Mara has the construction of a modern love story but is, in fact, a kinetic exploration of the blurred line between an artist’s life and work. When we first meet the pair, Matt (Matt Johnson) surprises Mara (Deragh Campbell) as she hurries towards the door of her classroom. From her furrowed brow and overall countenance, we can immediately tell she’s uncomfortable with his presence. He tells her he’s back in town and wants to meet with her. In quick response, she lets him know she’ll be in touch via email and proceeds to enter the lecture hall. The film then cuts to the beginning of Mara’s lecture for a poetry class and her shifting attention to Matt tiptoeing into the classroom and clumsily looking for a seat. Mara smiles, and we can sense that these two have known each other incredibly well, despite the tension in their interaction in the opening scene. After Mara’s class, the duo head to a cafe where they talk about the ideas that they are creatively reflecting on: Matt is trying to find proximity to characters in his writing that are far different from himself, and Mara is interested in a protagonist who “truly believes that they know nothing about themselves and that all of their desires are complete secrets from them.” We learn more about the past dynamic between Matt and Mara from conversations Mara has with one of her colleagues as well as with her husband, moments that are interspersed between scenes of Matt and Mara in the present. With Matt back in Toronto after an extended period in New York, the two friends frolic and play around on the city’s sidewalks, get passport photos taken, attend a party at the house of Mara’s department head, and visit Matt’s comatose father in the hospital. The pair are radically different, but together, both have a vibrancy and warmth with each other that is noticeably different from their relationships with others in their respective lives. And yet, Mara’s own uncertainty with herself and Matt’s false extroversion that distracts away from his lack of confidence eventually come to a head when Matt chaperones Mara to a conference, and both writers are forced to assess their relationship with each other as people, not artistic personas. With Matt and Mara, Kazik Radwanski exhibits a refreshingly contemporary understanding of communication, action, and intimacy and where they all break down, making Matt and Mara one of the most sharply resonant and observant films that we saw this year. You can read a full review of Matt and Mara here

• •

Algo viejo, algo nuevo, algo prestado (Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed) / Argentina / dir. Hernán Rosselli

With his hybrid-fiction crime film, Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, director Hernán Rosselli creates a visually diverse and complex low-budget feature that is as innovative in its inception as it is thoughtful in its construction. Utilizing ideas from his own familial experiences, along with surveillance footage, news reports, and the home videos given to him by his longtime Lomas de Zamora neighbor (and ultimately the star of his film), Maribel Felpeto, Rosselli cleverly composes a fictional narrative on a family’s illegal gambling business that blurs reality in a similar fashion to our own memories through the use of the aforementioned varied media elements. The plot is centered on Maribel, who, along with her mother Alejandra (portrayed by Maribel’s real-life mother, Alejandra Cánepa) and some trusted allies, attempts to carry on the their clandestine bookmaking operation after the sudden suicide of the family’s patriarch, Hugo Felpeto. While attempting to stay two steps ahead of federal officers, who are systematically raiding gambling dens all over the country in defense of the growing national lottery, Maribel is tasked with destroying any documents that could be found incriminating in a raid and breaking into her late father’s laptop to see if he moved any money to secret accounts. This search by Maribel through her father’s online accounts turns up evidence of her father’s extramarital activities, which prompts her to search for answers that, when found, leave her questioning everything from her family’s structure to her own identity and purpose. Operating as the central narrator, Maribel’s thoughts are effectively matched throughout the narrative with the real-life home videos shot by Hugo that primarily serve to paint an affecting portrait of her mother’s transformation from an intelligent, but naive fiancée to the decisive and ruthless leader whom Maribel was raised to emulate. Through the use of surveillance footage that provides emotional distance and also foreshadows the raid that will shutter the family’s business forever, we as the audience become less concerned with a dramatic outcome, leaving us free to examine how our perceptions of reality are formed when we are inundated with a barrage of misleading stories about and by the people we trust throughout our lives. Take a look at our full review of Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, which was published here on Ink 19 on December 9th.

• •

Universal Language / Canada / dir. Matthew Rankin

When we viewed Matthew Rankin’s debut feature, The Twentieth Century, we were immediately charmed by his idiosyncratic style of overlaying farce on top of a selection of events in Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s life. The bizarre but vibrant aesthetic of the film, hearkening to Futurism, German Expressionism, and Surrealism filtered through the Golden Age of Television proclaimed the Winnipeg-born director as a clear descendent of Guy Maddin. This lineage is reaffirmed with Rankin’s second full-length, Universal Language, but the director introduces the influence of an additional parent, Iranian cinema. Universal Language reimagines Winnipeg as the Tehran of Canada, a place where the beige architecture and snow of one of the world’s coldest cities live side by side with the city’s Persian culture and dominant language, Farsi. The film tells two tales and gathers them together with an enthusiastic tour guide who shows people the marvels of Winnipeg. One of the stories pays homage to Jafar Panahi’s White Balloon: two sisters (Rojina Esmaeili and Saba Vahedyousefi) roam the city looking for an ax to excavate money frozen in ice in order to pay for the replacement glasses of one of the sister’s classmates. And, in the other, a man — played by Rankin himself as a nod to the tradition of Iranian directors playing themselves in their own films — leaves Montréal and returns to Winnipeg only to find that his mother’s exact whereabouts are a mystery as his childhood home has been sold and is occupied instead by a kind family. Meanwhile, the tour guide (executive producer and co-writer Pirouz Nemati) emphatically highlights Winnipeg’s modest sights such as its abandoned mall and a forgotten briefcase that no one has ever taken or opened, which has become a city landmark as an emblem for human honesty and trustworthiness. The characters roam around Winnipeg’s streets and sidewalks seeking completely separate things, but, gradually, their paths move closer to each other and lead them to the tour guide’s apartment where revelations transpire. By superimposing Tehran on Winnipeg, Rankin implicitly raises issues around autonomy and independence inherent in the tensions between Canada’s Anglo and French origins while also noting the multiculturalism of Canada that accelerated in the twentieth century. The Winnipeg of Universal Language is as foreign to Montréal as Paris is and vice versa, but both cities are related through their history, particularly by Louis Riel, whose monument is notably featured in the film next to a highway. Born in Saint Boniface (which is now a part of present-day Winnipeg) to a Métis father and French-Canadian mother in 1844 and educated in Montréal, Riel founded the province of Manitoba and fought against the Canadian government’s attempts to take over Métis land in the region. His charge of treason and subsequent execution catalyzed a rise in Québec nationalism in the late 1880s, which, in the century to follow, gave rise to the Québec sovereignty movement. Riel thus embodies Canadian plurality, and the scenes featuring his monument stress this concept that is dear to the film and its filmmaker. Universal Language envisions an entirely Persian Winnipeg, but in doing so, it demonstrates how we, despite our divisions, are inextricably linked in ways seen and unseen, and there’s something lovely and amazing about that.

• •

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Bên Trong Vỏ Kén Vàng) / Vietnam, Singapore / dir. Phạm Thiên Ân

A sinuous road film flowing with sensorial delights, Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell takes us from Saigon to the Lâm Đồng province in Vietnam’s Southern Central highlands where the director Phạm and his cinematic analog, Thiên (Lê Phong Vũ), grew up. In the earliest parts of Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, we observe Thiên moving listlessly through his life in Saigon: he edits wedding videos in his small apartment; he hangs out with his friends; he gets a massage. Phạm, along with his cinematographer, Đinh Duy Hưng, present these moments in long takes, allowing the audience to see what’s happening around Thiên and how it all fails to inspire any activation from him. When Thiên’s young nephew Đào (Nguyễn Thịnh) manages to survive a motorbike accident that kills his mother, Thiên suddenly becomes Đào’s guardian and takes on the duty of bringing his nephew as well as his sister-in-law’s body back to their shared hometown in the countryside. Once the van that he hires for transport out of Saigon arrives at Lâm Đồng, Thiên is reimmersed in the physical and the spiritual landscape that he had left behind. The service for his sister-in-law is held in the Catholic church that he attended as a child. And, he is surrounded by the lush mountains of the highlands and a constant mist and fog, evoking a mixed sense of the mystical, primordial, and holy. The long takes continue here, but Thiên is noticeably more aware and pensive as figures and moments from his past re-emerge and lead him to embark on a mission to find his brother, Tâm, who departed years ago on a spiritual mission with destination unknown. Thiên rides his motorbike and walks on mountainous roads, and his upward movement physically parallels his ascension of metaphysical planes. Navigating between multiple dualities — reality and dreams, city and country, earthly and divine — to render the complexity and beauty of the spiritual quest, Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell is a highly accomplished debut feature that remained in our minds throughout 2024. We had the privilege of speaking with Phạm Thiên Ân at the beginning of this year about his Camera d’Or winning film. You can read that conversation here.

• •

SUPPLEMENTAL FILMS

Anora / USA / Sean Baker

It’s too easy to simply reclassify Sean Baker’s Palme d’Or-winning feature Anora as a modern and more realistic reimagining of one of the most inept and insulting Hollywood films ever made, Pretty Woman. Sure, the setup is virtually the same…A streetwise sex worker from the wrong side of the tracks comes to know a wealthy John who pulls her into a world of privilege she never dreamed of, and it all seems grand until the straights complain about the woman of a questionable past, and it becomes a fight to end the affair. But, with its torrid pace, central characters, and, most importantly, the silent growing camaraderie between its central characters who are put into an impossible situation that reflects upon their place in New York City, Baker remarkably manages with Anora to draw an unlikely comparison to one of the finest genre masterworks of 1970s American cinema, Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon. Here, the titular Anora (Mikey Madison) is, in her voice and attitude, the pure embodiment of many generations of Brooklyn rolled into one. A descendant of Russian immigrants, Anora lives in a second-story working-class apartment with her sister, where she sleeps during the day and works as an exotic dancer at night at a less-than-opulent men’s club. On one of those nights, she is commanded by the club’s owner to utilize her Russian language skills in order to attend to Vanya (Mark Eydelshteyn), the spastic adult son of absent oligarch parents who have left their boy in the States with just a palatial mansion and an unlimited expense account to keep him entertained while he skips out on college. Always up for a good time, Vanya requests that Anora come to his estate for a paid sexual encounter, which then turns into a party invitation and a request to exclusively escort him for a week, leading to some casual hangs and an airplane ride that lands the pair in Vegas for a quickie wedding.

It’s all starry-eyed for a moment for the newlyweds until they head back to New York, where the beleaguered paid assistants of Vanya’s parents, Toros (Karren Karagulian), Garnick (Vache Tovmasyan), and Igor (Yura Borisov), race to the mansion to send Anora packing. Once at the mansion, though, the goonish trio subdues Anora after a long, drawn-out fight, and Vanya, ever the cowardly brat, runs away, leaving his bride behind. For the remaining two-thirds of Baker’s film, Anora, Toros, Garnick, and Igor frantically race through a frozen NYC on a desperate and, at times, comedic search for Vanya, and it is this grouping of broken individuals, who should be constantly at one another who come to realize that they are all, by their lot in life, stuck in this miserable situation in an unforgiving city, that pulls Anora into the same universe inhabited by Sonny, Sal, the scared tellers, and even the cops of Lumet’s sweltering summer bank heist film gone wrong. In the end, like Dog Day Afternoon, Anora ultimately benefits from stunning, unique performances that fuel the well-written characters in each film to wholly depict New York City in their respective eras as a place where anything can happen, but where the majority of its citizens are struggling under the thumb of a power too strong to overcome.

• •

Youth (Spring) / France, Luxembourg, Netherlands / dir. Wang Bing

Carved from 2,600 hours of footage, Wang Bing’s Youth (Spring) exhaustively considers the cyclical nature of the terms of its title as expressed by the everyday moments of teenagers and young adults working in small factories in Zhili City, approximately 150 kilometers away from Shanghai. For each year’s garment making season, which begins in colder months and ends sometime in spring, the young from rural provinces travel to Zhili City to make children’s clothing. Each factory produces a set of styles determined by the managers and owners, and payment for each laborer is based on a pattern’s complexity and the total number of pieces sewn by the end of the season. The work is undoubtedly grueling, but the workers manage to find life and do the things that newly emerging adults do: bicker and fight, fall in and out of love, play video games, scroll on phones, hang out with their friends and colleagues, and find creative ways to bear each day of labor. The vivacity and wide-eyedness of the workers is not far from the spirit and energy of their university-bound peers, but Wang reminds us with small details — such as the decaying walls of the dormitories that house our laboring youth and the various social rituals performed around fetching water from industrial spigots to wash each night because the buildings are not equipped with showers — and the constant reiteration of miniature pants, dresses, jackets, and shirts being sewn and stacked, along with extended scenes of negotiation for better payment prices per style, that the factory setting is not a place of mind expansion and development: it is a vicious cycle where youth is commodified and cannibalized, leaving little promise of a different future for the children who will wear the clothes being manufactured. Much has been made about the over three hour runtime of Youth (Spring), but all of that time is needed because the minutiae and the high, low, and in-between moments from the workers’ lives show us how youth disappears not in a single grand event, but rather day-by-day, which is a heartbreaking tragedy that no one can stop, but one that we should avoid accelerating as much as possible.

• •

Los delincuentes (The Delinquents) / Argentina / dir. Rodrigo Moreno

There are two outstanding original Argentine crime films on our list this year: Hernán Rosselli’s harrowing hybrid-fiction essay that challenges our perception of family and identity and its comedic and ethereal counterpart from Rodrigo Moreno that reimagines the bank heist genre into a masterfully entertaining statement on the duality of man. The Delinquents begins with longtime bank employee Morán (Daniel Elías), a paunchy and balding middle-aged man whose visual appearance could easily meld into the corduroy couch of a 70s sitcom, getting ready for his work. One day, with the ease of a master criminal, Morán absconds from his place of employment with a few hundred thousand dollars in a satchel. Later that evening, he meets up with and blackmails his coworker Román (Esteban Bigliardi) to become a post-crime accomplice. The deal: Morán promises to confess to the theft after he returns from a trip out of town and will cut Román in for half of the money if he hides it for him while he serves a three-year jail sentence — the sum for each share of the loot equaling another twenty-plus years of drudgery in the bank. Unfortunately for Román, if he turns this opportunity down, Morán will name him as an accessory, leaving Román with no choice but to nervously stash the plunder in his flat without telling his adoring girlfriend. From this moment on, Román and Morán’s experiences existentially diverge and converge as Morán’s peacefully planned incarceration is rudely interrupted by his extortion-heavy cell block leader, who is, of course, played by the same actor who portrayed his bank supervisor (Germán de Silva), while Román flees to the countryside to hide the cash, where he meets the luminous pastoral Norma (Margarita Molfino), who unbeknownst to Román has previously shared a tryst with Morán (yes, anagrams delightfully abound here)! For its over three-hour running time that blithely goes by, The Delinquents thoughtfully shares notes of criminal symmetry and absurdity with Jarmusch’s Down By Law and yet still emerges as its own distinctly beguiling epic on greed and contentment, richly played through two characters who are the incomplete sides of the same coin.

• •

Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat / Belgium, France, Netherlands / dir. Johan Grimonprez

In the same way that jazz musicians come together to create a dazzling, intricate mixture of sound comprised of melody and rhythm, regrettably, so too did the Belgian monarchy, the US government, and a slew of corporations in January of 1961 to conspire to execute their insipid plot to delegitimize and kill the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba. As he did with his 2017 feature documentary Blue Orchid, which delved into the global arms trade, Belgian multimedia artist and filmmaker Johan Grimonprez once again turns his camera towards the unsavory underbelly of political maneuvering where lives are traded for profit with Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat. Drawing from the books My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, To Katanga and Back: A UN Case History, and Congo, Inc., here, Grimonprez expertly fuses everything from spoken word pieces to archival footage of the jazz that was performed by a who’s who of iconic artists who were sent by the US State Department to Africa during the 1950s and 60s under the guise of a goodwill mission that actually functioned as a smokescreen for covert operations to undermine post-colonial governments. Implementing a method to cleverly beguile you into a sense of nostalgic joy early in the narrative, Grimonprez and his team of editors enthrall you with a cascade of mesmerizing sounds and visuals from jazz legends, luring you into a state of bliss before steadily pulling the carpet out from under you when the onerous details substantiated through various forms of hard evidence paint a grotesque and calculated picture of America and Belgium’s joint mission to preserve access to Africa’s vast mineral resources, resources that the US feared were slipping away when many of Africa’s nations began to, one by one, unify, strengthen, and pull away from their colonial oppressors. As Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat details the actions of an American propaganda machine that sought to turn every message of support for Africa’s first post-colonial nation into one of fear and Communist rhetoric, the film thankfully calls out the few brave western artists who caught wind of the plot to dismantle Lumumba’s government who subsequently boycotted being used in the campaign, and so, as the plot unfolds and these musicians and activists express their disdain, the music responds in kind by moving away from bop and into sounds of protest from the Africa that incorporate the continent’s many original rhythms. Given the ambitious nature of the entire composition of Grimonprez’s film, one may fear that the method might overwhelm the subject at times, but instead, the inevitable death of Lumumba still hits hard as it’s presented here, as an outro for the piece that draws a line towards a present-day Congo where dour campaigns continue by governments who now vie for that nation’s coltan, a mineral required to power today’s electronics.

• •

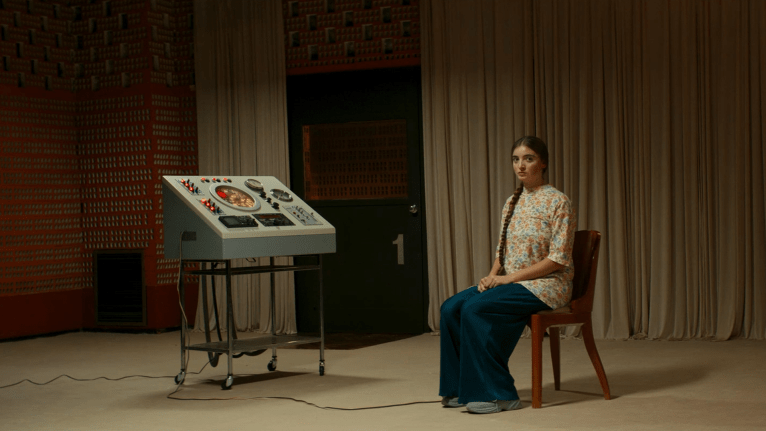

Yeohaengjaui pilyo (A Traveler’s Needs) South Korea / dir. Hong Sang-soo

Considering the seemingly effortless nature of their previous collaborations, it is a surprise that Isabelle Huppert and Hong Sang-soo have only worked together twice in the last dozen years. As seen in 2012’s In Another Country and 2017’s Claire’s Camera, Hong’s immense adoration for Huppert fills the duo’s latest joint project, A Traveler’s Needs, and his absurdist setups continue to showcase Huppert’s considerable talents as a comedic actress. Huppert portrays Iris, a French woman whose mysterious mission in South Korea leans on a method she recently developed to teach the locals her native tongue in order to pay for a portion of her stay, and although she has doubts about her system’s capacity to facilitate language learning, her eccentric nature allows her to test it on anyone who is open to giving it a try. Iris, whose fanciful manner of speaking hangs perfectly inside of a Hong Sang-soo frame, asks her clients to share their most personal thoughts as part of her quasi-remedial process, and after having lengthy discussions with the student in English, Iris writes a succinct synopsis of the ideas and thoughts that emerge in French and requests that the student recite it repeatedly into a tape machine prior to their next meeting. Hong presents two lessons with two different pupils, and within both sessions happens an unprovoked musical performance executed in a lifeless fashion by the students who identically critique their own poor proficiency and admit the desire to have better skill with the same exact words. Iris includes these musical incidents with her students’ disclosed thoughts in the French sentences she gives them, but each line exists as her own reflection on them and commentary on their lack of self-awareness. Each of these statements composed by Iris thereby act as a vehicle for Hong’s criticism of his own people’s desire to constrain art with precise and rigid execution instead of allowing it to flourish with joy from the act of expression and inspiration from the elemental. To this end, Hong carefully distinguishes Iris’s wardrobe from that of the people around her: others mostly wear neutral shades, but Iris wears a delightful springtime nymph inspired ensemble featuring a bright pink floral dress and grass-green sweater, which blends as easily into a park’s landscape as it does into a green terrace where Iris pauses for a rest, suggesting that she is a representation of the natural flow that needs to be embraced by those around her. Alternately, when the scene shifts from the pastoral to the confines of Iris’s apartment bedroom, where she is serenaded by the piano-playing of her flatmate, a poet named In-guk (Ha Seong-guk), Iris’s attire changes to suitably match the room’s warm tones as she persuades her friend and willing benefactor who is allowing her to stay for free to not over fixate on the notes he needs to play next and instead focus on the present sound. But soon, this thoughtful and gentle moment between two friends is interrupted by In-guk’s mother, whose insecurities and unreasonable desire for safety are directed towards her son as she casts doubt on Iris’s wholesome intentions. This dire moment between In-guk and his mother in the final third of A Traveler’s Needs radically shifts the film away from the whimsical and into an even starker cultural statement by Hong of his own people’s reluctance to relinquish their need for control, which suppresses their capacity to connect with their emotions and, in the long run, hinders any meaningful form of expression. The success of A Traveler’s Needs can be largely attributed to Huppert, who gives Iris several dimensions with a single look and contributes significantly to the most recent chapter in Hong’s post-COVID output, which once more features our director issuing a sobering wake-up call to those asleep in complacency in the face of an uncertain future.

• •

Bai ta zhi guang (The Shadowless Tower) / China / dir. Zhang Lü

For his fourteenth feature, Sino-Korean director Zhang Lü presents a subtle and poignant examination of urban loneliness, memory, and reconciliation with The Shadowless Tower. As the title suggests, the Miaoying Temple, with its looming pagoda erected in the thirteenth century in Beijing’s Xicheng district, is known by locals as the “tower without shadow,” as its architectural design allows the absence of a visible imprint on the ground below from any angle. Serving as the tower’s personified center is Gu Wentong (Xin Baiqing), a middle-aged divorced food critic and father of a young daughter who leads an otherwise stable, but emotionally distant life that will soon be pulled into several different directions. On the occasion of the second anniversary of the passing of his mother, Wentong receives news that his long-estranged father has been keeping tabs on him and his sister via his sister’s husband, Li (Wang Hongwei), who has kept this secret for decades. Wentong, now with his father’s nearby address and phone number in his hand, considers a possible reconnection. Concurrently, he develops a cautious relationship with Ouyang Wenhui (Huang Yao), a pixie-like young photographer who takes pictures of the restaurant food to accompany Wentong’s articles and is drawn to him by a great respect and admiration for his writing. The pair spend ample time together in various locales around the city, and although Wenhui is blissfully youthful and expressive, Wentong remains subdued and polite, but when Wenhui admits that she is from Beidaihe, where his father Gu Yunlai (portrayed by the brilliant director of The Blue Kite, Tian Zhuangzhuang) currently resides, he suggests they take a trip there. Once they descend on the beach town, Wentong gently stalks his father while he is out and about, going as far as to tour his apartment when his father is not home, and Wenhui unknowingly befriends Wentong’s father during his regular kite-flying sessions. Wentong tries to better understand his father by looking through the few items in his modest apartment, and when his father returns, Wentong has left, but the father senses his son’s visit and proceeds to leave treats for him, an act of recognition and hope that he will return. These dreamlike and lovely scenes of skewed unspoken reconnections are some of our favorite moments from The Shadowless Tower, and they eventually culminate in an actual reacquaintance between father and son facilitated by Wenhui that sheds light on Yunlai’s absence from Wentong’s life, a reveal that may help Wentong to look inward and reconnect with the world around him. Elegantly lensed by Piao Songri, The Shadowless Tower explores characters in their environment as few films did this year, offering us a skillful and thoughtful commentary on post-COVID urban alienation in modern China.

• •

Louis Riel or Heaven Touches the Earth (Louis Riel or Heaven Touches the Earth ) / Canada, Mexico / dir. Matías Meyer

Few genres in cinema are as hackneyed and overwrought as the biopic. And funny enough, we have two quasi-biopics in our list this year, Quentin Dupieux’s Daaaaaalí! and Matías Meyer’s Louis Riel or Heaven Touches the Earth. While Daaaaaalí! is a parody of the making of a biopic that becomes an essay on the creation of the fantastical artistic and public persona that was Salvador Dalí, Meyer’s foray into the form is a personal reflection on one’s own ethnic, national, and spiritual identity as an outsider channeled through the legendary Canadian figure, Louis Riel, leader of the Métis people and founder of Manitoba. The director, like Louis Riel, speaks English and French fluently, is close in age to Riel during the time period captured in the film (in fact, during production, Meyer was only one year older), is also from a Catholic culture, and has similar spiritual beliefs grounded in the connection between nature and God. At this point, you may have some expectations of a conversational film between Meyer, the director, and Riel, the subject, but let us make it clear that Meyer never directly discusses any of his own experiences in Louis Riel or Heaven Touches the Earth. The director does, however, play the titular character/historical figure and reads Riel’s own diaries and writings throughout the film, Meyer’s first feature directed outside of his home country of Mexico and in Canada instead, where he’s lived since 2011. Louis Riel is one of the most written about and chronicled figures in Canadian history, and consequently, determining which part of Riel’s life to study is a challenge. Meyer selects the period of Riel’s imprisonment prior to his execution for treason and focuses on his messianic visions, reconciliation with the Catholic church, and articulation of the spiritual legacy he’d like to leave for his children and people. The director presents to us a meditative Riel preparing for the end of his life, making Louis Riel or Heaven Touches the Earth less concerned about specific biographical details and more interested in portraying Riel’s state of mind. Hence, the film navigates between Riel’s earthly existence and his heavenly projections, and what makes it particularly commendable is its discipline in tone, which is consistently reflective and never dramatic as Riel’s turmoils in life are quieted by his own thoughts into a place of peace. We had the opportunity to interview Matías Meyer prior to the premiere of the film at FICUNAM 2024. You can read that conversation here.

• •

Daaaaaalí! / France / dir. Quentin Dupieux

It’s been seventeen years since the release of Steak, the directorial debut feature from Quentin Dupieux (a.k.a. Mr. Oizo), and since Steak, we have been treated to a dazzling array of wildly imaginative surrealist comedies that usually find their way into our favorite film list year after year. Of course, as we’ve been admirers of his work, which usually stars a modest cast of exceptionally talented actors, we were beyond stunned early this year when we read that his film, The Second Act (Le Deuxième Acte), featured the A-list talents of Léa Seydoux, Vincent Lindon, and Louis Garrel, and was selected as the opening film at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival! For a director whom we’ve often viewed as an idiosyncratic outsider, we wondered how Dupieux could prepare for that thrush of mainstream attention. Perhaps the most astute way to pre-humble oneself for the glare of the spotlight is to construct a portrait of an artist whose immense popularity in his lifetime helped to foster a media persona that would, at times, outweigh the impact of his work: Salvador Dalí! First premiering at Venice in September of 2023 and released here in the States this fall, Daaaaaalí! is a sublimely narratively scrambled seventy-seven-minute snapshot of the personage of Dalí, which, despite its short running time, could not be portrayed by simply one actor but five: Eduoard Baer, Jonathan Cohen, Pio Marmai, and a couple of Dupieux’s usual suspects: Gilles Lellouche and Alain Chabat. The film’s setup has Judith (played by another of Dupieux’s regulars, Anaïs Demoustier), a pharmacist turned documentarian who has scheduled an interview with Dalí for print, which he hopes/expects/demands as a documentary piece, complete with giant cameras and microphones. Eager for a chance at a big break, Judith agrees to a filmed conversation, which is again aborted by Dalí, who destroys the camera. This is then followed by a third meeting where Dalí insists on interviewing Judith, much to the ire of her short-tempered producer, Jérôme (Romain Duris). Eventually, the overwhelming amount of Dalí’s machinations incorporates Judith, and the film is led down paths-a-plenty that are rapidly reimagined, from desert sojourns to killer cowboys to trips to Hell to Dalí repeatedly imagining himself as an elderly Dalí, all in service of the creation of the Dalí celebrity monolith. Despite its dizzying tangents that purposely fragment in multiple directions, Daaaaaalí! is a disarmingly funny poke at the timeless art of self-mythologization, a practice that is all too common and far less entertaining in our constantly connected and documented lives.

• •

BEST REPERTORY/RESTORATION SCREENING

Coup de Torchon (Clean Slate) / France / dir. Bertrand Tavernier

As devoted fans of Jim Thompson’s novels, there has been a long-running conversation in our home around the sharpest cinematic adaptations of Thompson’s work. Back in 2020, we were treated to the sublime 4K restoration of Série noire, Alain Corneau’s rarely screened take on Thompson’s A Hell of a Woman, and earlier this year we rewatched another of our favorites, James Foley’s 1990 compelling go at Thompson’s After Dark, My Sweet, but inevitably, the debate ends at Coup de Torchon, Tavernier’s radical transformation of Thompson’s Pop. 1280, which rises high above the rest. Cleverly, Tavernier, along with legendary screenwriter Jean Aurenche, extracted Thompson’s bumbling, ineffectual, cuckolded, Southern cop and placed him deep into the misery of 1938 French West Africa to create an occasionally grotesque black comedy that takes dead aim at the inhumanity inherent in colonialism. The wonderful Philippe Noiret commands the film as the philandering, corrupt police chief, Lucien Cordier, who embraces his public role as the town fool only to obfuscate his true self, that of a nihilistic and calculating killer who is more than willing to execute anyone who opposes the moral code that he himself has created. Step by step throughout Coup de Torchon, Cordier becomes the human personification of a colonial government. At first, he appears to carry with him the formal code of justice from his homeland, but as time goes on and the absurdist nature that he and his fellow countrymen represent in this foreign land where the locals have become nothing more than exploited labor, Cordier becomes more hypocritical to his own code of ethics. A last spark of rational hope comes for Cordier in the form of a comely French school teacher, who embodies the good of all that is the homeland’s culture, yet she too becomes another blight for our police chief that makes his colonialist cancer complete with a body count formed out of the mutation. Noiret, who excelled in Tavernier’s L’Horloger de Saint-Paul (The Clockmaker) and La Vie et Rien D’autre (Life and Nothing But), delivers his finest and most emotionally complex performance in a very unsavory role for the ages. The Cleveland Cinematheque screened the new 4K restoration of Coup de Torchon in March, and we thank them immensely for the opportunity to see one of our favorite films of all time restored to new brilliance.

Featured photo courtesy of Epicmedia Productions Inc.

Lily and Generoso Fierro