I promise that this is my last Dash Shaw review for a while. I’ve been anxiously awaiting the release of Doctors, and alas, I have it and have been unable to maintain my patience to reasonably space out my reviews of Shaw’s books.

Of the Shaw works I’ve read so far, Doctors has an unsettling cynicism and darkness about it. Bottomless Belly Button and 3 New Stories contained some comments alluding to the occasionally malevolent and duplicitous nature of people but not to the degree of Doctors. Perhaps this change in tone is the product of the topic discussed in Doctors: death.

Cover of Doctors

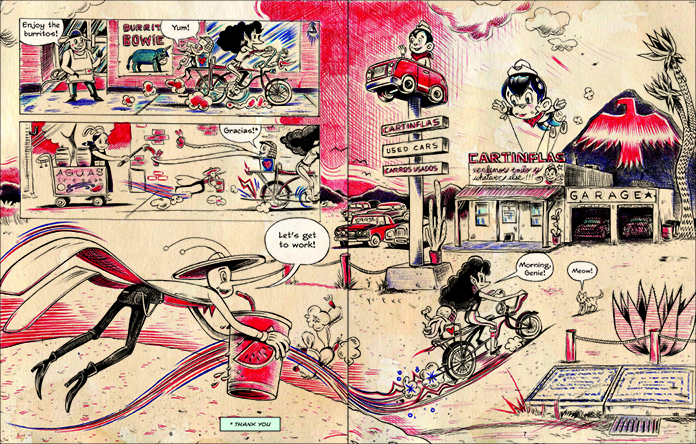

Despite the general existential tone of Doctors, the overall narrative still has the absurd and occasionally comically strange moments characteristic of Shaw’s style. Doctor Cho and his daughter, Tammy, run a laboratory where they test the Doctor’s invention, the Charon. For a hefty fee, the Cho lab can bring a loved one back from the dead when they are in an intermittent afterlife between death and the final end known as “the fade to black.” When we enter the world of the Cho family business, they are in the midst of bringing back Miss Bell, a wealthy widow who died suddenly and whose daughter, Laura, would like back in the world.

Even though the Charon and its capabilities suggest that Doctors is a science fiction work, the device itself is hardly the subject of the narrative. The short novel contains short fragments from multiple narrators, ranging from Tammy to Will, the lab assistant, to Miss Bell, with each story describing the history of the character and building up to their current intersecting point in the revival of Miss Bell. And to add an additional layer of cleverness to the book, each fragment in the book is drawn above a different color to remind the reader of each different perspective and the changes over the course of each page.

From Tammy and Will’s perspective, we understand the severity and seriousness of their work: They are defying the rules of nature and do not quite understand how to tackle the consequences. What does not help is the callousness of Doctor Cho, a naturally distant man made more insensitive and cold by the murder of his wife. Unlike Tammy and Will, Doctor Cho looks at the Charon as purely a lucrative business, a way to make a lot of money with technology without considering any emotional disturbances experienced by the revival process of his invention. The Charon is simply a solution to a scientific question for Doctor Cho. Could he bring someone back to life from the dead? Yes, and that yes is all that matters to him.

On the opposite side of the Charon experience, we see Miss Bell’s attempt to re-integrate into her life after her revival. Unfortunately, her return to life is not quite what she had hoped. After her death, Miss Bell, in the intermittent state between death and nothingness, created an afterlife where she was in love and no longer alone; for the first time since her husband’s death, she felt joy and youthfulness again. Upon being ripped out of this pleasant state, Miss Bell is thrust in front of her attorney by her daughter to settle the details of her estate, which is a beyond disappointing welcome back message.

Gradually, Miss Bell’s psychological state degrades as she realizes the bleakness of her reality as compared to her afterlife. Rather than returning to warmth and love from her daughter, Miss Bell returns to her life as a lonely widow pent up in her house. Laura is not around and only seems to appear when money is involved, and Miss Bell longs for her previous afterlife, trying to seek elements to re-create it in her current reality.

At the heart of all of the trajectories of each character in Doctors is the question: If you bring back a loved one, is that going to be better for the individual than death? The Charon, in concept is a nice idea, but in execution it is not because those brought back to life already have death programmed to occur again, and conflicting decisions to dodge or face that second death lead to crippling mental instability, making the revival useless except for having the revived sign paperwork. Consequently, what is the value for the creators and the users of the Charon?

In addition, with the examination of Charon patients such as Miss Bell, a major philosophical question for scientists emerges: even if you can create or access a device that defies nature, should you use it? Inherent in the answer to that question is hubris. Doctors is somewhat of a tragedy, for Doctor Cho and Miss Bell’s daughter Laura exhibit the greatest amount of hubris, and they are met with tragic ends that damage their loved ones. They both believe they can overcome death to get what they desire without realizing that perhaps what nature intended was the correct course in the first place, and in turn, endure the most severe consequences of the Charon.

By the end of Doctors, you are left asking yourself who is more evil in this scenario, the scientists who create the nature defying device or the people who pay exorbitant amounts of money to use it for selfish purposes? I’m not entirely sure, but there is definitely some shared responsibility for the ill-fated consequences of toying with forces one does not understand. Doctors, on an initial read, feels like a naturalist piece of writing, but by the end, everything bad seems to fade away and life for the more accountable Will and Tammy seem okay but pretty directionless and meaningless in general, making the story much more of an existential one. Thus, if everything most likely means nothing, who is the most evil in the story? Who is the most irresponsible? Who is the most selfish? Who is the most myopic in their actions? What is the afterlife? What is death? Would you want another moment with a loved one who has passed on if achieving that moment could harm them? Those questions are much harder to answer in an existential world, and Doctors definitely will not point you in any direction, but it will make you think more carefully when you do attempt to answer them.

Doctors is now available via Fantagraphics Books.