After two readings of Inio Asano’s Nijigahara Holograph, I, like many other reviewers that tackled the 2014 English translation of the collected chapters of the seinen manga originally released in parts from November 2003 to December 2005 in Japan, will admit that I may not completely understand the series. However, absolute comprehension does not prevent any enjoyment of this tale; in fact, it mostly relies on an ebb and flow of guttural reactions ranging from repulsion to somber recollection in the best Takeshi Miike way but with a bit (though not much) more anchored in reality.

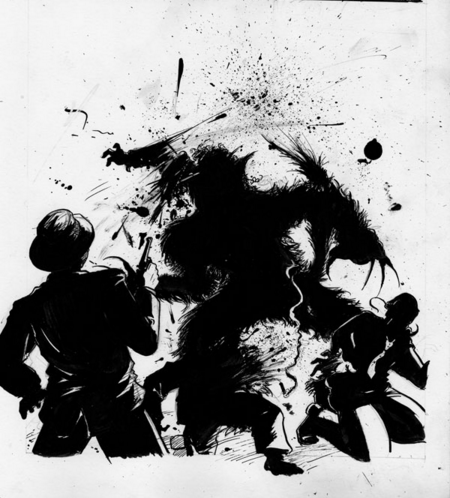

Cover of the English Volume of Nijigahara Holograph

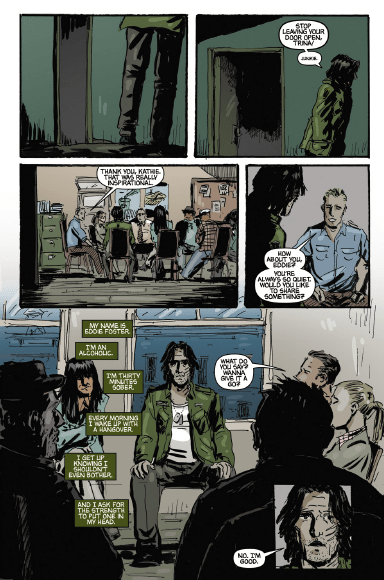

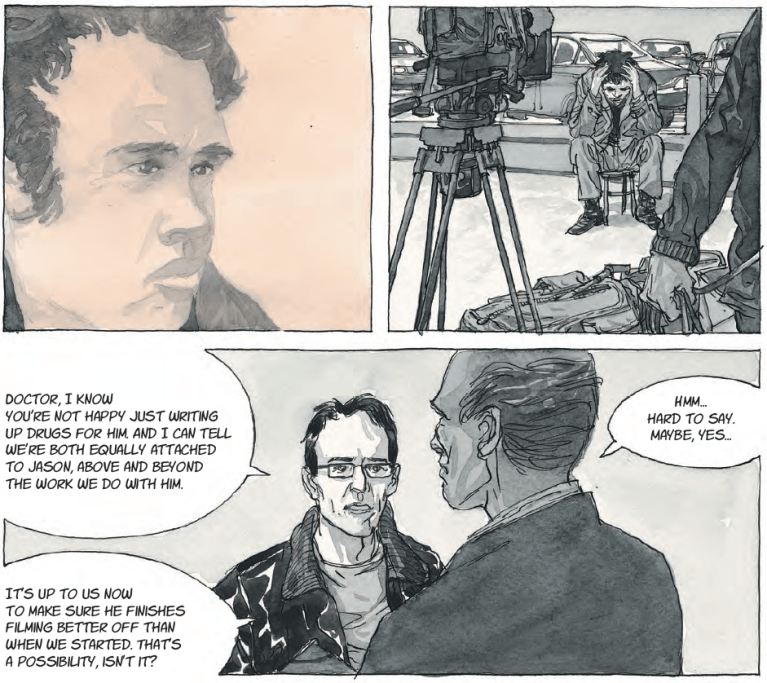

Opening with butterflies, a boy walking on the exterior of a school, and then a young man speaking about his ill father and the merging of reality and dreams to an elderly man whose face we cannot see, Nijigahara Holograph immediately distinguishes itself from what the West generally expects from manga. Expect no adolescent scantily clad women here; in fact, leave any hope for romance or lost love or even any bit of catharsis at the door. The world of Nijihara Holograph is severe, bleak, and unforgiving, and every single character suffers for his or her own actions or for the sins of others. This is not a read for the faint of heart.

The Eerie Second Page of Nijigahara Holograph

Time has no constancy in Nijigahara Holograph as ghosts and memories of the past never fade away: beyond the flashes we see in the minds of the characters, the evils of the past have a physical manifestation as glowing butterflies that swarm the city. As time unravels in the novel, so does reality, with everything in the present clouded by recollections, dreams, hallucinations, and even a touch of prophecy fulfillment. While the different characters have their own branches and paths that occasionally intersect, their arcs remain rooted together by Airé Kimura, a young woman who has remained in a coma in the local hospital since childhood. Airé prophesied the end of the world via a monster in the Nijigahara tunnel, and the people around her did not believe her and caused her harm by attempting to sacrifice her to the monster in the tunnel.

Airé is not new to the world; her spirit has transformed multiple times, with each version warning the surrounding world about the apocalypse to come and each message of caution receive with skepticism and distrust. The citizens of the village murdered Airé’s previous incarnations, but in the most recent cycle, after a majority of her classmates push her down a vent that ends in the tunnel fated to have the monster, Airé survives, but she remains unconscious through her adolescence and early adulthood. This permanent state of sleep keeps Airé safe from the world around her, away from the various predators who have either psychologically or physically attacked her, but it also keeps her force present on the earth. While life has remained quiet for most of the people who crossed paths with Airé, with her classmates growing uneventfully into adults and teachers having families as they approach their early 40s, an energy of dysfunction and hysteria has recently descended on the town, causing macabre scenes of violence and various, seemingly unconnected journeys toward the Nijigahara embankment, the entry to the tunnel that contains the creature of the apocalypse. An awakening to Nijigahara will arrive soon, and as the time approaches, more and more butterflies spread across the town and begin to consume people connected to Airé in one way or another.

While Asano alludes to philosopher Zhuangzi’s well translated and studied quote about the philosopher’s dream or reality as a butterfly, whether or not all of Nijigahara Holograph captures the dreams of Airé, her childhood friend Kohta, or Amahiko, the student transfer from Tokyo who never met Airé in person but who may have encountered her spirit, remains unclear by the end of the series, but whether everything occurred under dream logic or not is unimportant to Nijigahara Holograph, for the actions in the series speak as gravely in dream form as in reality about the cyclical desecration of purity through violence, cowardice, and fear.

Highly experimental in its image and story construction, Nijigahara Holograph creates a unique mood of dread with its sudden juxtapositions of visual beauty of Airé and the butterflies against the most abject and abominable acts of human will. As a result, the feelings of desperation and futility do not stem from Airé’s declarations of the impending end of the world; they come from the abject nature of the humans which gets passed on from generation to generation without a clear end in sight. This cyclical nature of pain, torment, and the destruction of beauty drives the world of Nijigahara Holograph, making the idea of the apocalypse paradoxically welcoming because while it does end life, it finally will end suffering generations of people have inflicted on each other.

More of a punch in the chest rather than a distanced, ruminative read, Nijigahara Holograph demands and consumes all of your attention. It challenges your own perspective, thoughts, and dreams along with the definitions and conventions of the comics and manga medium, making it a sobering read in the first week of the new year. While I still feel that I may not understand all of the layers of Nijigahara Holograph, I do know that it encourages me in 2016 to dig deeper for comics that test the boundaries of storytelling, and for that inspiration alone, I am grateful to Inio Asano, even if this work accomplished a remarkably overwhelming sense of gloom and desolation in its exploration of some of the deepest, darkest crevices of our collective hearts and minds.