World War I is gradually disappearing from the American collective memory. The history that remains is passively stirred up on a few occasions with History Channel’s specials and books such as Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet On the Western Front, with both highlighting the devastation by the technology introduced to make WWI the the first impersonal and massively destructive war. However, most children only skim over WWI in history classes, focusing more on WWII, given its even larger annihilation of human life and its opening of the age of weapons of mass destruction. Consequently, most common knowledge about WWI only exists around the introduction of gas warfare and the crippling German defeat that would eventually fuel the rise of National Socialism.

Written from the perspective of an infantryman on the frontline, “Happy Days!” by Alban B. Butler, Jr. documents the daily lives and occurrences of the First Division during WWI, beginning with their journey to Europe in 1917 and ending with their return home in 1919. Unlike most historical retellings of WWI, the grisly details of the war are almost entirely avoided. As a collection of cartoons written for the the men of the First Division and their daily trench newspaper, the First Field Artillery Brigade Observer, “Happy Days!” provides nearly one hundred snapshots of the little moments of absurdity, insanity, and silliness in the war, all hoping to deliver a laugh to the men battling in dire conditions against difficult forces and weapons.

Cover of “Happy Days!”

From the absurdity depicted in the cartoons, Butler’s work reminds us that WWI was not a war where the United States was at its pinnacle as a world power. Men had to adapt to trench warfare, the French language and culture, multiple nation armed forces, and new weapons to protect oneself with but also to protect oneself against. With all of these new things to learn and understand, there were plenty of mistakes, mishaps, and altogether poor planning along with strange but effective procedures and protocols, creating a point of comedy for Butler’s cartoons to occupy.

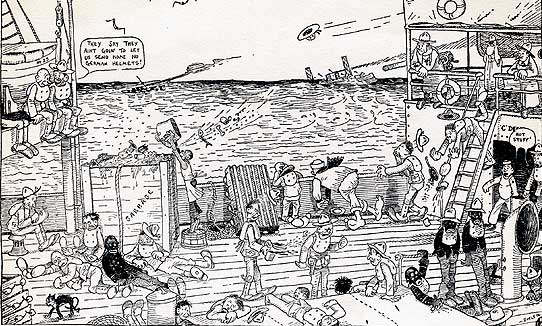

Ranging from horse races with sated horses that were excessively fed after being starved due to a prolonged journey in harsh climate to the firing celebration on the 4th of July by the Division for the French forces’ acquisition and delivery of gas shells, Butler documents the endless humor existing in many of the soldiers’ activities. Although the cartoons certainly stand alone, what really makes “Happy Days!” special is the additional commentary included with each cartoon about the context of its creation. With the cartoon and the commentary, each page of the collection feels like the diary of Alban Butler, making the reader feel much closer to events occurring almost one hundred years ago.

Life in the Trenches from Butler’s eyes

In addition to Butler’s work, the introduction, preface, and afterword all provide further context for Butler’s cartoons, making the book a perfectly packaged moment in history. Arguably, “Happy Days!” may be interpreted by a modern eye as pro-morale propaganda for soldiers, but each cartoon has the voice of a soldier addressing something of specific concern or interest, making each cartoon feel as if it were created after hearing soldiers speak in the trenches or in a mess hall.

As a result of its distinct voice, “Happy Days!” contains a different, more personal perspective on WWI. While it is essential for us to remember and learn from the wreckage of WWI, it is also important to understand the people who lived, worked, and served our nation in it. Through comedy but not satire or allegory, Butler reminds us of the absurdity of the war while allowing the reader to relate to the men who were in it. The men of the First Division valiantly served in a war where a lot of inexperienced people led and fought on both sides, but they also had their own lives outside of battle that are worth understanding and remembering now that war tactics and activities have deviated so far away from where they were at the beginning of the 20th century.

“Happy Days!” by Alban B. Butler, Jr. is available via Osprey Publishing and The First Division Museum at Cantigny.