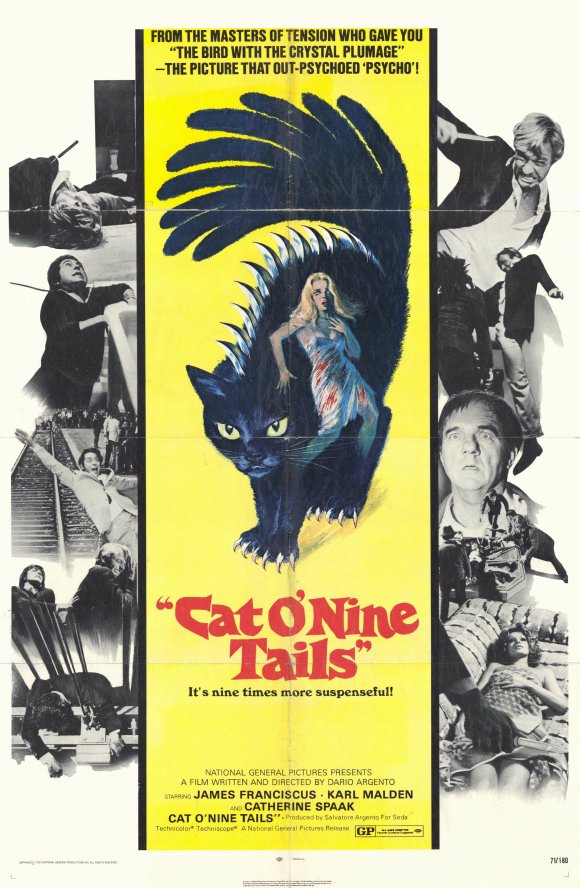

Before I write one critique about Dario Argento’s second film in his “animal trilogy,” “Cat o’ Nine Tails,” let me first commend him on casting the usually gruff talent of Karl Malden in the role of Franco “Cookie” Arno, a blind ex-reporter who creates crossword puzzles while taking care of his adorable niece, Lori. Sure, Malden is solid in this role as always, but the mind swims at the concept of Dario possibly sitting at his office and pitching to his producer/brother Salvatore that Malden would be perfect as the lovable Cookie, a year after Malden’s tough portrayal of General Omar Bradley in “Patton.” Either Dario is a genius, or Malden could just nail any part that came before him. I also wonder if Michael Douglas ever pulled the “Cookie” card on Malden the following year when they began filming “The Streets Of San Francisco?”

You might think that it is a bit odd that I am reviewing the middle film in a trilogy without ever reviewing the first and third films, but let me assure you that there is absolutely no connection between the three that might encourage you to watch Dario’s first in the series, “The Bird With The Crystal Plumage,” before reading further into my review. What is true about this period in Argento’s work is that it represents his thriller output before he would embrace more of the supernatural aspects that would define his later films. In “Cat o’ Nine Tails” you have our young director drawing from Hitchcock, as so many of his peers were, but here he adds that element of sinister violence that is less gory than his later masterpiece “Suspiria,” but still quite jarring at times, especially one very creative and teeth-clinching elevator-related death. Though not a masterwork, I found “Cat o’ Nine Tails” to be as solid a thriller as Argento would make at this point in his career.

Our story begins with a burglary occurring at a genetics lab and the sounds of this event being picked up by our darling Cookie, who becomes interested a la James Stewart in Rear Window, so he then teams up with a young and all too hunky reporter, Carlo Giordani (played by the rugged and coiffed American television star, James Franciscus). After a few folks associated with the lab start ending up dead, it becomes clear that the lab has discovered some genetic strand that bears out the criminal tendencies that lie within people, and they have also created a drug that can cure these bad thoughts, but someone isn’t thrilled with one of these two discoveries, so the bodies start to fall. As stated earlier, the murders are not of the lavish, glowing straight razor variety that you would come to expect from Argento; most of our victims in “Cat o’ Nine Tails” are dispatched in the rope around the neck style. This is fine by me as Dario tries to make the plot the star around our killings, as opposed to a sketch of a plot that exists just to glue together a series of baroque imagery as in many of his giallos. My only real stylistic complaint comes from the enviable sex scene between Carlo, our dedicated reporter, and the wealthy daughter of the genetic lab’s director, Anna (Catherine Spaak, the gorgeous lead from Dino Risi’s 1962 film, “Il Sorpasso”). I’m not sure why Argento insisted on filming their coupling in the most robotic way possible, but as an Italian man, I am a bit taken aback by such non-emotional touching that given the dire circumstances that those two characters were surrounded by, should’ve heated up their illicit tryst.

Kudos again to Dario for the attempt at plot complexity here, but it may just be a bit too complex as the “nine” in the title refers to the nine potential criminal leads that are never followed fully enough to potentially draw your interest away from the reveal of the actual killer making the ending, despite a stunner of a death scene, fairly anticlimactic. There is also a score created by legendary composer Ennio Morricone, that is pretty lackluster, which is not surprising considering that Ennio has scored over five hundred projects over his illustrious career. There has to be a few throwaways in the bunch, and sadly we have one of those here. Malden and Franciscus are the main reasons why you stay in your seats as they are veteran actors that can make any scene work a cut above the rest.

Original 1971 Trailer For Cat o’ Nine Tails

“Cat o’ Nine Tails” is a decent enough film that now stands as a kind of testing ground for a young Dario Argento for what would and would not work and not work in his subsequent films. There are more than enough visual creations that will make you jump, and the overall cinematography is more than a cut above the usual early 1970s giallo. Finally, I tip my hat to director Argento for acquiring the acting talents of Malden and Franciscus for this, only his second feature film. I don’t know if I would have the nerve to fly an actor the stature of Malden across the Atlantic and saddle him with a character named “Cookie,” but I still admire Argento for thinking that Malden would fit into that character so well.