He will have passed by her, right by her without really noticing her, because she was one who gives no clues, who has to be questioned patiently, one of those difficult to fathom. Long ago, a painter would have made her the subject of a genre painting…

Seamstress

Water girl

Lacemaker

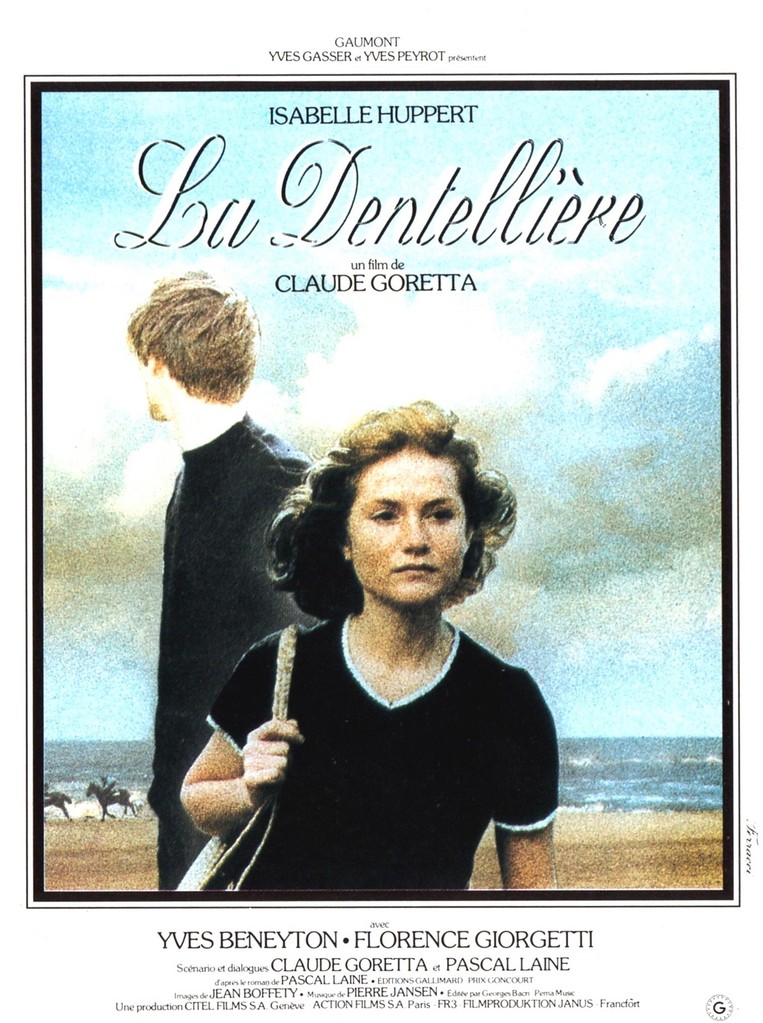

The lines above roll up screen at the end of Claude Goretta’s 1977 film, “The Lacemaker” and are there to sum up Beatrice, a naturally beautiful and shy young woman in a Parisian hair salon where she works as the shampoo girl and occasionally sweeps up the clipped hair. Beatrice lives with her mother, a lovely middle-aged woman who, like her daughter, lives a quiet, unassuming life without apparent joy or anger. Though Beatrice’s dad left them both when Beatrice was still a small child, both mother and daughter go through their days appearing content and relatively unfazed by everyone and everything around them. This setup is similar to that of his previous film from 1974, “The Wonderful Crook,” where Goretta creates an almost too peaceful environment before showing the small cracks in the armor of his characters and their surroundings. With “The Lacemaker,” Goretta has shifted from the pastoral French countryside to an almost overly serene Paris where our protagonist will soon be faced with options for her life, which to this point could be the life of a thirteen year old and not a young woman.

In an early scene, we see Beatrice at the apartment of the comely Marylene (Florence Giorgetti), Beatrice’s closest friend at the salon. Beatrice watches Marylene’s world come apart as she achingly ends her three year relationship with a married man over the phone. Marylene, overwhelmed with grief, threatens suicide via her apartment window, but, instead, she opts to toss out the over sized teddy bear gifted to her from her lover, serving as a comedic sacrifice that establishes Marylene’s flighty character. Still sour over getting dumped, Marylene drags Beatrice for company to the French coastal town of Calbourg during the off season to help get over her ex lover. Once in the sleepy town, the women immediately go to their hotel room, where they listen to the couple next door in mid-coitus, which seems to only mildly embarrass Beatrice and somewhat turn Marylene on to the point that she asks Beatrice to turn down the radio. Goretta leaves Marylene’s sexuality as somewhat ambiguous as she seems to have a somewhat romantic bend towards her friend, but it becomes very clear that the chaste Beatrice has no desire to be outwardly amorous with anyone. After a couple of trips to the local discotheque where Beatrice refuses to dance with male suitors, Marylene hooks up with an American man and abandons Beatrice for the remainder of their vacation, which again does not effect Beatrice in the slightest. Here, one begins to wonder, if anything will make Beatrice finally react positively or negatively. The only pleasure that Beatrice indulges in is chocolate ice cream, which she eats alone until she meets Francois (Yves Beneyton), an awkward, scrawny and slightly older literature student who awkwardly engages Beatrice in conversation. The pair do not exchange contact information, but in one of the best scenes in the early part of the film, they each spend the entire next afternoon trying hard to casually meet again, which they do. With Marylene nowhere to be found, Beatrice and Francois spend every day together, and after Francois proposes they spend the night together, Beatrice, as she does with everything proposed to her, goes along with it, and they becomes a couple.

Once back in Paris, Beatrice and Francois find an apartment together, and after a brief conversation with Beatrice’s mother which ends with “as long as she is happy,” the young couple are off to start a life together in a modest (tiny) Parisian apartment. I need to establish something that I think is key before this world comes crashing down: Director Goretta shows in more than a few scenes that the couple are actually in love; although it is never said, Francois is at times overwhelmed with affection for his woman. I believe that this moment is key as the conflict that will soon arise from Francois’ rapid growth as a budding pseudo-intellectual university student will cause doubt in his mind as to the adaptability of his new found love. When a colleague of Francois’ arrives before Beatrice gets home from work, Francois begins to describe her to his friend in the same way that a teacher would talk about a elementary school student rather than a fully formed adult in regards to potential. You begin to believe at this point that Goretta may begin to make an overarching statement about the anti-humanist tendencies of academics, but it doesn’t go in that direction as Francois’ intellectual friends appreciate Beatrice for who she is and believe that she is good for Francois, who seems to be regarded by them as emotionally closed. You might also believe that this is a setup for demonizing the character of Francois, but that is not Goretta’s intention either, nor is it his intention to paint Beatrice as a dolt. They are both portrayed sympathetically, but their conflict as a couple becomes more a question of being content with one’s own persona. Simply put… Beatrice is content with her passive existence, and Francois, who clearly loves Beatrice, is not content with any of his roles of his own life, as a son, a boyfriend, or as an academic and projects his insecurities onto Beatrice.

As I stated in an earlier review of Goretta’s “The Wonderful Thief,” the Swiss-born Goretta does not simply attack class as Luis Buñuel would in “Diary Of A Chambermaid,” for example. Though Goretta and his writing partner Pascal Lainé on “The Lacemaker” initially create characters who have simple desires, they also create an environment that exposes the smallest discrepancies in those characters, which allows their transformations to occur naturally if you notice their faults. Such is the case when Francois invites Beatrice for dinner at his parents home. Goretta takes painstaking efforts setting this scene up for the viewer. Francois’ family home, once stately, is now rundown. His parents have a servant, as any good upper middle class family would, but she acts more familiar with her employers, further indicating that the days of their historically held wealth are most likely in the past. Francois’ fear (or perhaps hope) that his parents will reject Beatrice are unfounded as his father takes an immediate liking to Beatrice, whereas Francois’ mother is colder but not condemning of his relationship in any way. Again, there is not a class war happening here, since the only person who is unhappy with Beatrice, is Francois, because he is not happy with anything about himself.

Original Trailer (no English subtitles, sorry!)

Goretta leaves nothing to chance with “The Lacemaker” in selecting every facet of his character’s world, and just as he did with The Wonderful Crook”, Goretta formulates early pleasant scenes to allow you to calmly gather your feelings towards his protagonists before leading you to a tragic ending when you suffer with all involved. Once the screen fades to black and the statement that I posted at the beginning of this article appears in front of you, it is painfully clear that the beauty that Francois wants to posses in Beatrice has always been in demand for many generations and that perhaps the beauty comes with a passivity that you must allow to continue for the beauty to stay intact.