Between November 23rd and 26th, we lost three very distinct talents who were the creative forces behind some of the most innovative films of the 1970s: Nicolas Roeg, Bernardo Bertolucci, and Gloria Katz. During these three days when each of these artists passed away, we were in the process of writing the below list of our favorite films from this year and needless to write, but the conversations we had about these filmmakers’ works at the times of their deaths greatly influenced the selections that we made.Therefore, in keeping with these artists commitment to evolving the language of cinema, we feel that the films that we have selected from our feature film viewing from 2018 made valiant and substantial strides in moving cinema forward. We dedicate this year’s best of list to Roeg, Bertolucci, and Katz, and we cannot express enough our deepest thanks for their films that have meant so very much to us.

We would also like to thank the following organizations for programming the cinema that made this list possible: The American Film Institute’s Festival, The Acropolis Cinema and their Locarno in Los Angeles Festival, The American Cinematheque’s Egyptian and Aero Theaters, and the Central Cinema.

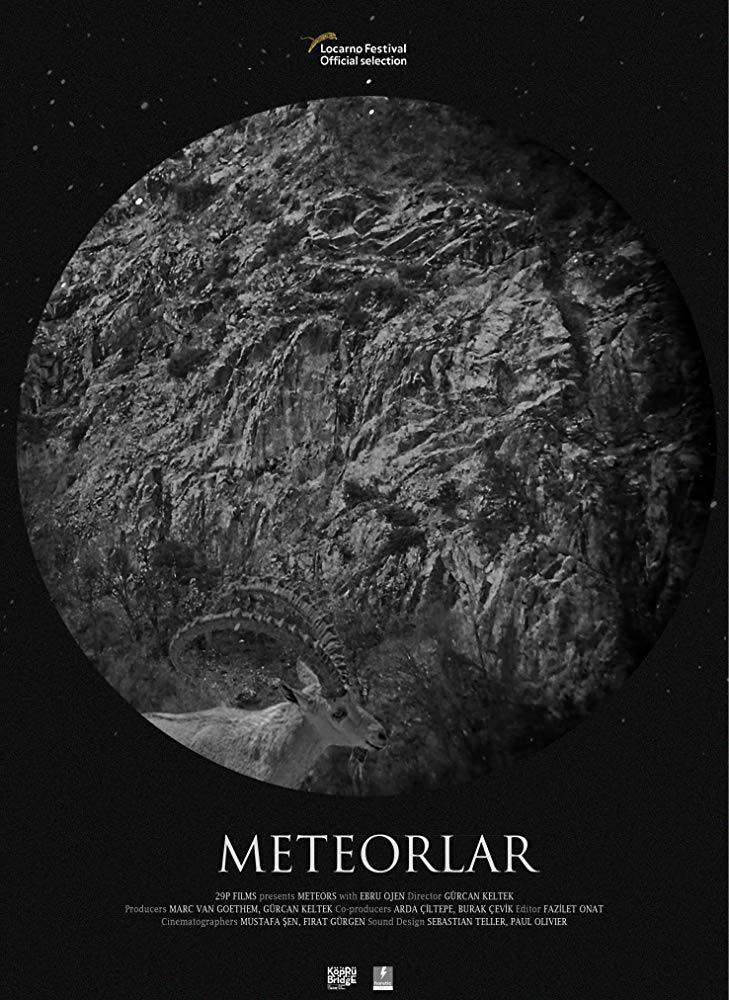

1. Meteors (Meteorlar) / Turkey, The Netherlands / dir. Gürcan Keltek

Weaving together scenic and tumultuous images from nature with footage of people in the midst of political action and violence, Meteors stunningly and repeatedly layers these images on top of each other to form an elaborate discourse about the transient, fleeting nature of peace and violence in our societies and in our world. Director Gürcan Keltek uses two specific political events, the Turkish military’s breaking of a ceasefire with the Kurdish Workers’ Party and the Women’s Initiative for Peace, as starting reference points to capture the emerging political landscape of conflict in southeast Turkey. With the footage from these events, Keltek lures you into believing that Meteors will be a political film that will offer first person insights into the context and climate of these events, but when the images of hunters and prey, meteor showers, and even a solar eclipse takeover, and no deep explanations of the political conflicts are given, a larger conceptual discussion rises, asking the question: “Is violence a fundamental part of nature?” While the footage of aggressive moments across species (humans of course included), suggests that violence is inherent in our nature as animals, Keltek’s deft intertwining of more tranquil, meditative images reminds us that even though violence is part of us, we can have peace. Thus, like a meteor falling to earth, violence, though it catches our immediate attention, can and must fade, and it is our responsibility to remember that peace, like the meteor before it burned into non-existence, did exist and that the beauty of peace is something to be preserved, since we know it will end.

2. Occidental / France / dir. Neïl Beloufa

We saw Occidental in the first weeks of 2018, and it stayed as a highmark for us throughout the year. Nonchalant in its political ideas, audacious in its visuals, and purple-pink-soaked throughout, Occidental is a claustrophobic film of collisions that all take place in one night at the Hotel Occidental. With its set built entirely in director Neïl Beloufa’s studio, Occidental’s images are meticulously constructed with the hope that every character, every object, every sound will evoke a reaction from the viewer. Clashes based on race and ethnicity, gender, and sexuality emerge, simply based on how different characters interact with each other, and the film maintains an unwavering hysteria from a prolonged feeling of entrapment due to the political uprising happening outside the hotel and the possibility of some terrorist activity inside the building. What makes Occidental exceptional is one very basic thing: you cannot look away from it. Beloufa, who is primarily a sculptor and installation artist, throws everything he has at Occidental, and the outcome is a piece of art that has the visual mystery of an installation with a deceptively minimal narrative that makes you want to soak yourself in its intriguing glow and not leave until Beloufa forces you out.

3. Zama / Argentina / dir. Lucrecia Martel

Based on the novel of the same name by Antonio di Benedetto, Lucrecia Martel’s first feature since The Headless Woman in 2008, is set on the coast of Paraguay in the late 1700s. Zama explores the grotesque legacy of European colonialism in South America by witnessing the mental collapse of Don Diego de Zama (Daniel Giménez Cachoa), a Spanish officer, who fruitlessly awaits his transfer to Buenos Aires. Our protagonist saunters through one borderline surrealistically hideous example of imperialist exploitation after another and descends on a course of continuous rejection as he visits his other Spanish compatriots who never fully accept him, as he is not of Spanish birth, and as Zama’s mood declines, so grows the cards against him as he is severely disciplined by his superior officer and then rejected by the indigenous woman who gives birth to his child. Martel’s bold storytelling devices are the true strength of the film, as she incorporates hallucinatory visuals and sound constructed into intentionally overlayed conversations so that you can share Don Diego’s psychedelic journey into madness. Just as Martel masterfully did with her central figure in The Headless Woman, with Zama, she has created a film that expresses a sharp social statement while delving so deeply into her central characters minds as they sense everything falling apart around them that you feel the regret in every poor choice they make.

4. The Wolf House (La Casa Lobo) / Chile / dirs. Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña

Filmed in a single astonishing animated sequence, Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña’s feature, La Casa Lobo, is the story of Maria, a German-Chilean woman who hides from danger in a dilapidated house with two piglets. Using a storybook construction to amplify the insipidness of the horror Maria is trying to escape, the plot of La Casa Lobo is based on the abhorrent Dignity Colony in Chile, a secret society founded by Germans who left their own country after World War II. The Dignity Colony, which existed for almost forty years and thrived under Pinochet, operated a facility that detained and tortured political prisoners, and was founded by a former Nazi and child abuser, Paul Schäfer. León and Cociña’s particular technique evokes some of the eeriness that is present in the work of the Quay Brothers, which amplifies the ugliness inherent in this tragic moment in their country’s history. Nothing written here will do adequate justice to the brilliance of the visual elements of this incredible and affecting film.

5. The House That Jack Built / Denmark / dir: Lars Von Trier

Von Trier’s use of the grotesque pushes the limit on image-based studies of pain, which are all too common in today’s film and television. Today, we see many media studies that are so precise in conveying people’s pain under the veil of bringing attention to a social or political problem, when in reality, many of these media properties are simply created to appeal as banal eye-candy, or even worse, as exploitative imagery that is there to appeal to prurient or morbid interests. With The House That Jack Built, Von Trier deceptively pulls in the viewer’s natural desire to feed off of human misery to deliver a sharp critique of the creators (even going so far as to critique himself, and with the final scene of the film, the hubris that that consumes creators) of this type of media, and the audience members who devour it without conscience. The House That Jack Built is a must see for the fans of the Serial podcast and any other dramatized true-crime media who feel as though they are elevating themselves while thriving off of the pain of others, but ultimately are unaffected by their brief sense of thrill that they saw and heard a polished, non-offensive story about something forbidden (but really not forbidden). Von Trier throws at you all of the lurid images and sounds of murder that most crime-related media would avoid, and at the end, he mocks yours and his desensitization.

6. Burning (Beoning) / South Korea/ dir: Lee Chang-dong

It has been eight years since Lee Chang-dong’s eloquent and culturally critical feature Poetry, which has as its protagonist an elderly woman who attempts to enrich herself by taking poetry classes while desperately trying to solicit funds to compensate the victim of her grandson’s sexual assault. It is a searing critique of contemporary South Korea, and with Burning, Lee returns with a caustic statement about the loss of Korean identity for both older and younger generations. Loosely based on the short story by Haruki Murakami, Burning, like Poetry uses literary devices as its engine in stressing the importance of creating in a rapidly shifting world. Jong-su (Ah-In Yoo), a fledgling writer, runs into Hae-mi (Jong-seo Jeon), a neighbor from the same rural village where Jong-su grew up and now resides in while his father, a failing farmer, awaits trial for assaulting a government official. After an intimate encounter, Hae-mi asks Jong-su to look after her cat while she’s on a spiritual trip to Africa. During Hae-mi’s absence, Jong-su develops feelings for Hae-mi, but when she returns, she arrives with Ben (Steven Yeun), an enigmatic young man of mysterious wealth who will come to represent the soulless realty of contemporary South Korea. Like Andrey Zvyagintsev’s 2017 masterwork, Loveless, Burning is a flawlessly executed allegory that cuts deep into a society that values status infinitely more than art or humanity.

7. Diamantino / Portugal and USA / dirs. Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt

Considering the gravity of the myriad of crucial world issues addressed in directors Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt’s fractured fairytale of a feature, Diamantino, it is stunning to us that the whole affair chimes in at a mere ninety-two minutes and is as enjoyable as it is. The whimsical and somewhat Guy Maddin-esque narrative construction is centered on the titular character (played by Miguel Gomes’ favorite, Carloto Cotta), a Cristiano Ronaldo stand-in, who carries the hopes and dreams of his native Portugal on the pitch, whilst images of giant fluffy puppies dance through his head. Prior to his World Cup Final appearance, we find our Diamantino lounging comfortably on his yacht without a care in his gleeful skull with the one person who has truly adored our soccer star throughout his life, his pure-hearted and loving father. However, during this day on the sea, Diamantino is confronted by something he normally does not have to deal with, as approaching his pleasure cruise is the grim reality of the refugee crisis in the form of people who are clinging to life on the waters outside of his luxurious boat. This moment of reality has finally inserted something in the head of our football star that is not in the shape of a mammoth Pekingese, and due to this intense reality, Diamantino blows the penalty kick that costs Portugal the World Cup. What follows isn’t an existential crisis for Diamantino, but rather an acknowledgement that a far different world exists outside of his life and football, which leads our protagonist into a conflict between the need to do good for those around him by adopting a refugee of sorts and the instinctive, naïve response to blindly follow the commands of his older, twin-hydra evil sisters, with Diamantino’s siblings being utilized as a fitting representation of modern greed and anti-European Union/and anti-refugee movements. Abrantes and Schmidt frantically and comedically present to us a Europe that is now struggling with the divide between its more benevolent identity of the past, and the grim fact that a growing faction of the population wants to desperately close all borders and cling to a mythical version of a Europe that has only existed in children’s stories.

8. Once There Was Brasilia (Era uma Vez Brasília) / Brazil, Portugal / dir: Adirley Queirós

For the past sixty years, WA4 (Wellington Abreu) has been flying around the galaxy while dining on copious amounts of churrascaria, exiled after trying to squat on private land, but now, WA4 has been given the opportunity to legally acquire land for his family and to do so, he must travel to earth to assassinate Juscelino Kubitschek, the president who founded Brasília, on the day the city was to be inaugurated. Unfortunately, WA4 is desperately low on meat to grill and fuel, and crashes down in the middle of Ceilândia, a nighttime city on fire, where departing trains take away political prisoners. It is here where WA4 meets a colorful group of intergalactic space fighters (think Mad Max meets homemade Go Bots), who are hell bent on total anarchy as a political adjustment. Creatively drawing from the finest low grade elements of D-level science fiction films, and the cinematography of Joana Pimenta, who perfectly utilizes the darkness and burning to heighten the chaos, director Queirós uses the absurdity of his rickety homemade visuals and the unrestrained talents of his mostly non-professional cast to fuel a wildly inventive narrative that forces the viewer to experience the very real absurdity of contemporary Brazilian politics (Rousseff’s and Temer’s shenanigans are omnipresent here, of course). We are not sure if we have seen a better film so far this year that makes less so much more than it seems.

9. Happy as Lazzaro (Lazzaro Felice) / Italy / dir. Alice Rohrwacher

All is not well in the small village of Inviolata, a community that exists in a sharecropper state that has not been seen in Italy for generations. In Inviolata, we meet Lazzaro (played by seraphic-faced actor, Adriano Tardiolo), who is the gleeful recipient of two layers of exploitation. The primary layer comes from the Marchesa Alfonsino de Luna (how thrilling it is to see actress Nicoletta Braschi again, even as a villain), who uses the residents of the village to grow her tobacco that she sells at high profit, which keeps her and her family in the lap of luxury whilst the villagers barely subsist. And, the second layer comes from the villagers, who use Lazzaro’s puerile joy and motivations to mock him and to get the affable, good-natured Lazzaro to toil for them as well. The timeless and surrealistic quality of the narrative suggests that exploitation is not only a basic human trait, but also one that has and sadly will endure for generations to come. Biblical references aside (Lazzaro does translate into Lazarus, and the actions surrounding an encounter with a wolf loosely allude to the story of the Wolf of Gubbio that St. Francis tamed), Lazzaro functions in a somewhat similar way that Abrantes and Schmidt’s Diamantino and the Hae-mi character in Lee Chang-dong’s superb feature of this year, Burning, do, serving as an innocent, pure-spirited figure that allows the viewer to judge the evil around them more effectively. While Diamantino and Hae-mi offset malevolent societal imperatives of Portugal and Korea, respectively, Lazzaro functions to challenge the installation of morals through Catholicism. Furthermore, Rohrwacher, through her central character of Lazzaro, exposes a contemporary Italian population in economic freefall that is highly disconnected from its natural state due to its collective conscience’s reliance on guidance from organized faith and from government structures that have failed them over and over again. Using surrealistic elements that are more in tune with the hyperbolic Italian grotesque features of Ettore Scola and Marco Ferreri than those of the Italian neorealists to effectively amplify urgent issues to impact the audience more than any reality appears to do these days, Rohrwacher has made a heartbreaking and beautifully realized third feature film. Please check out Generoso’s interview with director, Alice Rohrwacher, on Ink 19

10. 3 Faces (Se Rokh) / Iran / dir: Jafar Panahi

Needless to write, it is always good to see any film these days that has Panahi’s name on it, given the governmental ban that has been imposed on him on producing any cinema. With a framework that offers a small, respectful nod to the late Abbas Kiarostami’s 1999 feature, The Wind Will Carry Us, 3 Faces has director Panahi and actress Behnaz Jafari playing themselves as they drive away from a film shoot towards a remote village after receiving an alarming video posted online of a young actress who commits suicide due to her inability to leave her hometown to attend the acting conservatory in Tehran. Once Panahi and Jafari arrive in the village, we soon understand the impetus of the suicidal actress’s thespian desire, as the young woman has befriended a reclusive actress who has been exiled in her home due to her work in pre-Revolution Iranian cinema. Absurdly comedic at points and clever in its utilization of an naturalistic metaphor involving cows, 3 Faces is an excellent companion piece to Kelly Reichardt’s 2016 feature, Certain Women, in that it exhibits the evolving role of women in society, and in turn, the resultant changing roles of men. In 3 Faces, the idealization of male gender roles is not progressing, and that is causing dangerous tension between men and women, and we see this tension compellingly play out in this small story that is expertly told by Panahi.

SUPPLEMENTAL FILM LIST

The Wild Pear Tree (Ahlat Agaci) / Turkey / dir: Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Delivering his first feature since his Palme d’Or winning 2014 film, Winter Sleep, Nuri Bilge Ceylan returns with his most personal film since his 2006 comedic gem, Climates. As many of his films are at least semi-autobiographical, here the Nuri role is filled by Sinan (Aydin Doğu Demirkol), a recent college graduate who returns to his rural hometown of Çan to live for a while in the home he grew up in, where his father (Murat Cemcir), an eminently-retiring teacher and notoriously bad gambler, lives in total disharmony with Sinan’s sister and mother. As a graduated literature major, Sinan has every intention of writing and publishing the great first novel, but in the midst of his decaying family, the young writer takes trips into the nearby town of Çanakkale for advice on his artistic ambitions, and the advice he gets comes from the local literary celebrity, who despite his success offers little more than cynicism, and as books need to be published with actual money, Sinan seeks potential funding from the local business head who offers Sinan advice on writing a book that would serve more as a guide for tourism. Throughout this engrossing, and at times humorous, 190 minute long Homeric journey, Sinan debates with himself his motivation for the creation of the novel he so badly wants to publish, and his experiences along the way include a telling phone conversation with a fellow literature classmate whose violent career choice is a reflection of the contemporary Erdoğanian Turkey, an illuminating conversation about how to interpret the Quran with two younger imams, and a constant witnessing of his father’s and his family’s movement away from teaching as a profession. In the end, The Wild Pear Tree becomes an interesting reflection for Ceylan at this point in his career, as the film cleverly references the director’s earlier features, most specifically, Clouds of May and The Town, works that harken back to the director’s original motivations for making art in the first place, and one wonders if the central message delivered in his newest feature is: given the state of his country, if that same young Nuri Bilge Ceylan was beginning his career today, would he even attempt to make a film?

The Nothing Factory (A Fábrica de Nada) / Portugal / dir: Pedro Pinho

Given the film’s subject matter of Portugal’s dire economic situation, and its forays into a multitude of genres during its three hour running time, it is nearly impossible not to compare The Nothing Factory, Pedro Pinho’s debut feature, to Miguel Gomes’ six-hour masterwork, The Arabian Nights, our favorite cinematic work so far this decade. Whereas The Arabian Nights uses individual stories, sometimes farcical, sometimes humanistic, to reveal the facets of Portugal’s economic problems and its impact on its citizens, The Nothing Factory mixes humanistic storytelling with the distant political overnarration and staging techniques of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet to form a story of about the reaction of a team of laborers who are stunned when they discover that the corporation that governs their workplace is sending in crews at night to steal machines and equipment from their factory before shutting it all down. One by one the workers are offered a redundancy package, which they know will only last them so long, and when it runs out, they will be forced to be look for work in a fiscally strapped Portugal that offers them less than nothing. Armed with this knowledge, our embattled workers do the only thing that they can do: refuse to leave their factory so that they can stave off the evitable for at least some period of time. There is much to love in The Nothing Factory, especially when the film steps away from its stylistic desire to overextend into a variety of genres in order to create an empathetic frustration and situational confusion for the viewer which is not always successful. The narrative thread that follows the path of one of the workers, a family man who ponders endless issues and yet still progressively turns into a leader, forms the most affecting scenes of The Nothing Factory, which has so much to offer in terms of real empathy for the people trapped in this grave situation.

Knife + Heart (Un Couteau Dans Le Coeur) / France / dir: Yann Gonzalez

The second feature by French-born director Yann Gonzalez, Knife+Heart is a stylish, inspired, affectionate look at the gay porn industry of the late 1970s as imagined by the director Gonzalez through a cinematic language that includes the pornography of that era, giallos, the excesses of Brian DePalma’s 70s output, and, most notably to us, William Friedkin’s 1980 film, Cruising, which despite the negative backlash from the gay community against the film at the time of its release, has come to be seen as a rare glimpse into an era and culture that would soon be destroyed by the AIDS epidemic in the subsequent years to follow. Knife+Heart centers on Anne (a perfectly casted Vanessa Paradis), a gay porn producer whose substance abuse issues have destroyed the one relationship that matters the most to her, that being her longtime affair with her editor, Loïs (Kate Moran). Even though Anne and Loïs’ relationship is broken, and a killer has begun to target Anne’s actors, the show must go on, and many of the best scenes in Knife+Heart develop from Anne’s new film approach, which weaves in the tragedy around her and her film crew to create her masterpiece, which drives our producer to hunt for the truth behind the murders of her actors, which may be hidden in the past lives of some of her crew and even herself. One of the most inventive, provocative, and disarming films to appear in the midnight programming of AFI Fest these last few years, Knife+Heart captures the distinct voice, style, and approach of Yann Gonzalez, a director whom we very much look forward to seeing more from in the future.

Dead Horse Nebula / Turkey / dir: Tarik Aktaş

Our favorite of this year’s selection of New Auteurs film programming at AFI Fest is Dead Horse Nebula, the debut feature by Turkish-born director, Tarik Aktaş. The story centers on Hay (Baris Bilgi) and begins with Hay as a child during his first experience with death when the boy discovers the carcass of a dead horse in a field and encounters life contained within the dead animal. Throughout Aktaş’ confident first feature, we see Hay’s interactions with death through the results of his passive and active role in the passing of life, but what becomes the core essence of the film is how past memories play a role in Hay’s connection to the natural progression of life leading to death. Dead Horse Nebula in tone is somewhat similar to Michelangelo Frammartino’s 2010 film, Le Quattro Volte, in the way that it allows the viewer to naturalistically gaze at the states of life, but whereas Frammartino’s film is about the transition of a life into other forms, Dead Horse Nebula excels in allowing you to see and hear the moments Hay experiences first-hand that build his perception of the natural world around him. Tarik Aktaş has created for his first feature, a carefully constructed and fully realized essay on the circular nature of memory and experience. Generoso spoke at length with director, Tarik Aktaş about his film and his process during AFI Fest 2018 for Ink 19.

MOST DISAPPOINTING FILM

Dogman / Italy / dir: Matteo Garrone

In a huge step backwards in his development as a filmmaker, Garrone’s newest feature Dogman selectively takes aspects of the very real and gruesome case of Pietro De Negri, a dog groomer, who murdered and mutilated a local thug who had been victimizing him over the years. What Garrone does here is little more than an emotionally and cinematically empty revenge film that neither makes a substantial social comment, nor is produced in a way that sheds any light on the original story. Save for Marcello Fonte’s performance as the titular character, Dogman is a disappointing follow up to Garrone’s 2015 feature, Tale of Tales, which was an imaginative treatment of Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone. The real crime of Dogman is that it was selected as Italy’s submission for the Best Foreign Language Oscar over some truly wonderful films from Italy this year, including Happy as Lazzaro.

BEST REPERTORY FILM EXPERIENCE

Burt Reynolds in Person at The Aero Theater, March 23rd, 2018 /Films Screened: Gator and The End

We have been fortunate that during our time in Los Angeles, we have gotten to be face to face with many of our cinematic heroes, and now, we should write that in no way should the following statement be perceived as one that diminishes any of those experiences, but the moment on March 23 of this year when Burt Reynolds, one of the last of great shining screen legends, and an actor whom we’ve admired our whole lives, took the stage at the Aero Theater in Santa Monica, our hearts, and the hearts of most of the audience, dropped a beat. Despite the cane he needed to walk, or the way time and lifestyle had taken its toll on his body, the smile and the attitude was all Burt, and we were so thankful to be in the presence of that man. The setup for this appearance and a few other Burt appearances that weekend was the release of a new film that 82-year old actor lent his talents to, The Last Movie Star, but given the widely reported state of his health, many of us in the crowd saw this as a chance to possibly say thank you for the final time. We sort-of didn’t care that the films that were screening on March 23rd were Burt’s directorial debut, Gator, a notoriously hot mess of a good ole’ boy smash ‘em up film, a genre that was made even more popular by Reynolds back in the day, and another Burt directorial effort, 1978’s The End (admittedly we love this one)–we were all just waiting for the screen legend’s comments during the Q&A session in between the two features, and here there was no disappointment. Burt seemed to light up when every question from an audience member was followed by some form of declaration of love, and he gave thorough, well-thought out, and grateful answers that showed a great deal of respect for the audience in attendance. The evening culminated when Burt, upon saying thank you, stood before the crowd for what seemed like ten minutes as people, many of whom were women, but to be candid a lot of men too (Generoso included), yelled out their undying love for Mr. Reynolds. Sadly, Burt passed away five months later on September 6th, but we are so thankful to the Aero for making this moment with Burt possible. Rest in peace Burt.

Burt Reynolds at the Aero Theater, 3/23/18, Photo by Generoso FIerro