Until the 1980s the word “apartheid” had been absent from daily speech here in America. Suddenly with growing attention from the western news, the anti-Sun City Movement, and films like “Cry Freedom,” “A Dry White Season,” and “A World Apart,” “apartheid” began to be a part of an open dialog in the USA. As a pre-teen in the late 1970s, I distinctly remember the first time that I heard the word spoken, which happened during an episode of the CBS drama, “The White Shadow,” a weekly series about a white coach of an almost all-African American basketball team in South Central Los Angeles. During one particular episode, Coach Reeves appoints the only white, but popular, player on the team, “Salami,” to be captain, which is fine with most of the team except for one player who speaks openly about the then current political situation in South Africa called “apartheid,” where the white privileged minority had been ruling the land without any members of the black African majority. The episode had left me curious, but even though I was growing up in a largely African American neighborhood in South Philadelphia, finding any information about apartheid at my local library was fairly impossible, that was of course until the middle of the subsequent decade when t-shirts declaring “Free Nelson Mandela” were seen everywhere you went in the city.

Even though the policies of apartheid had been established in after the general elections in South Africa in 1948, Hollywood had stayed clear of the subject until I assume it became a profitable “cause.” Finally, when television and film began depicting stories of this oppression from the last forty years, I became curious again, except this time I wondered if Hollywood had ever tried to tell these stories before during a period when it perhaps wasn’t in vogue to do so. The only example that stands out for me occurred in during the mid-1950s, when the massively underrated talents of director Richard Brooks touched on the subject in his film, “Something Of Value” which starred Rock Hudson and Sidney Poitier. Though the film was not about South Africa but Kenya, it successfully brought to the screen Robert C. Ruark’s novel of the same name about the real Mau Mau uprising that occurred in colonial Kenya during the 1950s. In that film, Sidney Poitier plays the African, Kimani, who despite being raised with his white friend Peter (Rock Hudson) has his father imprisoned by Peter’s father who protests Kimani’s father’s participation in a native Kenyan custom then deemed to barbaric by the colonial government. Outraged by his father’s imprisonment, Kimani joins an insurgency group called the Mau Mau that leads a bloody rebellion against the colonial leadership and eventually this forces Kimani to clash with his lifelong friend Peter. Though the film doesn’t directly address the situation in South Africa, it is Hollywood’s first and really only attempt before the 1980s (Brooks’ film was a box office flop) to expose American audiences to the growing political unrest in Africa stemming from apartheid colonial rule.

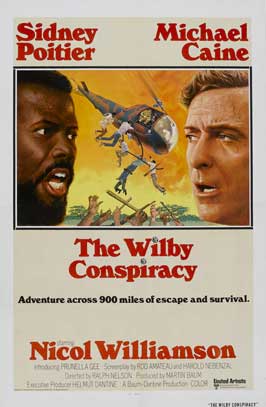

Twenty years later in 1975, Sidney Poitier is at his anti-apartheid ways again in the UK produced film “The Wilby Conspiracy,” an entertaining action film disguised as a political/cause thriller. What may have prompted the production of this UK film was that by the mid-1970s, mass paranoia was coming into vogue due to the Watergate scandal and Hollywood was frantically putting out political/anti-government thrillers with fairly complex plots such as David Miller’s “Executive Action,” Sydney Pollack’s “Three Days Of Condor,” and Alan J. Pakula’s “The Parallax View,” all of which were met with good critical and commercial success which surely prompted our friends in the UK to follow suit. “The Wilby Conspiracy” uses the apartheid situation in South Africa to run its plot, but due to the subject matter, filming was not permitted in South Africa and bizarrely the film would have to be shot in Kenya, the country that was the setting for Poitier’s earlier film, “Something Of Value.” Here Poitier plays Shack Twala, a jailed revolutionary who is released from prison at the beginning of the film by his Afrikaner attorney Rina van Niekerk (Prunella Gee) who has recently left her husband Blane (played by a very young Rutger Hauer in his first English speaking role), and she is now seeing British mining engineer Jim Keogh (Michael Caine).

Shortly after Shack’s release, the three are off to celebrate but are soon met by the South African police who hassle them for identification. When Shack, Jim, and Rita cannot produce the necessary ID needed, they are arrested but successfully fight off the police and make a run for it. Their arrest angers Major Horn (brilliantly played by Nicol Williamson who is best known to US audience as “Merlin” in John Boorman’s Excalibur) who chastises his second in command for not only his campaign of harassing black South Africans but also for arresting Shack, as his arrest will drive even more against the prevailing government. On the run yet again, Shack seeks out the assistance of Doctor Mukharjee (Saeed Jaffrey), an Indian dentist and fellow member of Black Congress. Soon Jim, Rita, and Shack are in the possession of a stash of uncut diamonds that will aid the Black Congress and their leader, Wilby (Joe De Graft), but, despite this success, they still must outrun the cunning Major Horn, who is still manically hunting them. You then have the necessary prerequisites for a 70s political action film with a few clever twists, a lot of very exciting car chases (Caine and Poitier were actually almost killed in one accident involving the car camera which became displaced), and even a bit of an unnecessary sex scene which is reminiscent of thrown in Dunaway/Redford tryst in “Condor.” Poitier and Caine do the absolute most given the fairly thin dialog which heavily leans on the buddy film tip, and they do produce some chemistry in their scenes together. Overall, the actors do a fine job, and script does provide a few laughs, but Nicol Williamson does steal the show as the intelligently written but villainous Major Horn.

“The Wilby Conspiracy” was directed with flair by American Ralph Nelson, who twelve years earlier had helmed the wildly successful and enjoyable nun extravaganza, “Lilies Of The Field,” which garnered an Oscar for his lead, Sidney Poitier, the first best actor Oscar awarded to an African American. Nelson would also direct Poitier and James Garner and hone his talents as an action director in the less successful but still entertaining 1966 western “Duel At Diabolo.” Through not possessing the intense drama of Brooks’ “Something Of Value,” Nelson keeps the pace quick in “The Wilby Conspiracy,” and with that fast pace he keeps up your interest in the story while never losing focus of dire conditions in South Africa at that time in history.

The Wilby Conspiracy Trailer

It would be almost a decade more before Hollywood would jump on the anti-apartheid bandwagon with their tear-jerking/heavy-handed offerings; films which now seem more concerned with preaching to a left leaning choir than opening up the discussion by presenting the situation in an action-driven political thriller format that would speak to a wider audience. Nelson’s film is illustrative about apartheid rather than didactic and thus, more effective in getting its core message out.