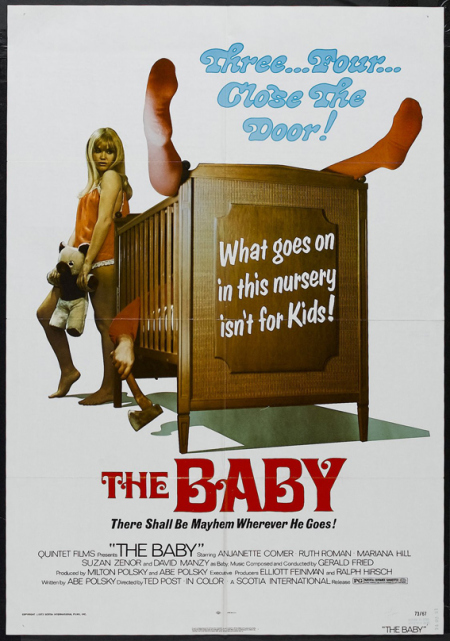

For his output in 1973, Ted Post may go down as having the single most wildly eclectic year for an American director. He scored a huge hit that year with “Magnum Force,” the second of Clint Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry” series about the somewhat racist San Francisco cop who shoots a lot of bad guys but still ends up pissing off his captain. Though critically panned, “Magnum Force” ended the year outgrossing the original film in the series by a bunch. Ted also directed a young hunky Don Johnson and Don’s soon to be mother-in-law, Tippi Hedren, that same year in The Harrad Experiment, a pseudo-serious sexploitation take on the best selling novel of the same name about a Dr. Kinsey inspired college where students are encouraged to do the horizontal cha cha. Much to no one’s surprise, “The Harrad Experiment” went flaccid at the box office. So, if you think that the two films I just referenced are wildly apart in themes, then allow me to introduce you to the third film that Mr. Post’s directed in 1973, a torrid tale of forced infantilism entitled, “The Baby.”

At the core of “The Baby” is bright young social worker Ann Gentry (Anjanette Comer) a dedicated young woman who gets the stunningly suburban Wadsworth family as her case. The Wadsworths have a “mother” for the ages (Ruth Roman); her two oversexed daughters, Germaine (Marianna Hill) and Alba (Susanne Zenor) and their brother Baby (David Manzy), a grown man in diapers who is enabled by the Wadsworths to live in a state of perpetual newborn. Ann’s response, being that she is a seemingly normal state worker who soon realizes that Baby’s disfunction is not physical but conditional, is to get Baby some therapy so that he can stop sucking his thumb and pooping himself in his massive crib. A crazy idea indeed, but mother always knows best and soon mother Wadsworth puts an end to Ann’s wild idea of turning her son into a grownup who could potentially leave the home and have a life of his own or at least a son that doesn’t need his bum bum talced thrice daily. I guess if our hero Ann investigated a bit further she could’ve had Baby legally taken away from the Wadworths, what with his sisters occasionally supplying Baby with sexual enticement and the odd poke from a cattle prod. No, this isn’t just maternal instinct gone Munchausen syndrome, it’s more like a reversal of Baby Jane done during the feminism movement. By 1973, the Vietnam war had been going on for over a decade, and women finally were expressing a desire to be something more than a baby machine. Most importantly, an entire generation of men had been taken away, and I guess the ones that were left to look after the women weren’t seen as the epitome of the manly man, and thus we have it’s most extreme example, Baby.

You would think that all of the above activities in “The Baby” would define it as a dark comedy. I mean, we are talking about a draft aged male prancing around in diapers while a family of almost human Stepfordesque women simultaneously nurture and torment our grown infant into further regression, but you never feel okay enough to laugh at this because somewhere in all of the exaggerated moments is the horrifying thought that this behavior shown on Baby most likely didn’t start last week, and that it is a systematic routine of going back to Baby’s actual infancy. You suddenly think back to Alba’s freewheeling use of the cattle prod on Baby as being done on an actual newborn, and the goings on don’t exactly bring one to giggles. If director Post’s goal was to show a new generation of feminist women who look at a child as an albatross, then the point is well made here in a frenetically unfunny way. You have Mrs. Wadsworth as the matriarch who hails from a past generation, a woman can only see herself as a mother and her young daughters who are reviled by the thought of motherhood. Even our young social worker Ann, who appears loving and concerned is hiding a pretty big skeleton in her closet as well.

“The Baby” 1973 Trailer

A scene that truly brings home the notion that Mrs. Wadsworth is beyond seeing herself as a sexual being and just a mother as any woman would from her generation is the birthday party for Baby. Mrs. Wadsworth gets a ton of attention from the men at the party (who by the way don’t seem remotely bothered to be there to celebrate the birth of man baby), but she soon shrugs off that attention as she remains mommy, first, second, and third. After a decade of young men going off to Vietnam and not coming back or coming back broken, Mrs. Wadsworth has created her own version of the perfect man. A “man” who will always need her, and one who is going to be with her for ever and ever. “The Baby” was promoted as horror in the same way that Larry Cohen’s baby-gone-psycho film, “It’s Alive” was promoted a year later. And although “The Baby” doesn’t pack the visceral punch as director Cohen’s film, it still has enough cringeworthy moments to nestle it firmly into that genre more than just pure satire. I guess that generation had lots to fear from the newborn, whether that newborn be big or small. As for this generation, I immediately wondered if “The Baby” would play well as midnight cult film or would a screening end up like it did in our home, with confused looks and muffled giggles and a bit more than a little concern for why this film was made in the first place.

More than the feminism movement, America’s participation in Vietnam effected almost every film genre from action, to romance, to yes, the family horror dramas as is the case with “The Baby.” A few years later, our director Ted Post to a look at the beginning of our involvement in Vietnam when he directed “Go Tell The Spartans,” a film about a US Army major, played by Burt Lancaster, who goes to South Vietnam in the early 1960s as an advisor who immediately begins to understand that our growing presence there would be a futile effort that would just get a lot of Americans killed. Perhaps it was our major who had a talk with with Mrs. Wadsworth that encouraged her to go into the eternal-baby making business?