Richard Pryor Takes The Wheel in “Greased Lightning.”

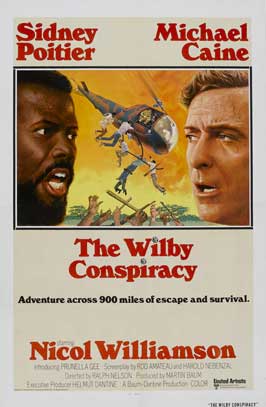

Michael Schultz was one of the most successful African-American directors of the 1970s. Starting out in television as a director for the early part of the decade, Schultz graduated to the big screen in 1974 directing Diana Sands in “Honeybaby, Honeybaby,” a low budget action film that was to be Sands’ last film before she passed away in 1973. Schultz immediately returned with the successful 1975 film, “Cooley High,” a entertaining high school comedy/drama that many refer to as the “Black American Graffiti.” In 1976, Schultz hit it big with “Car Wash,” one of the many “workplace comedies” of the 1970s that was inspired by Altman’s “M*A*S*H,” and a film that also produced a number one soundtrack for the disco era. That film contained about eight minutes of a rising comic named Richard Pryor, who sometime between filming and release developed into a star after nine years of small parts (with the notable exception of 1″The Mack”) in over a dozen films. Schultz rushed out to cast Pryor in the lead role, and so in 1977, Schultz cast Pryor in a US remake of Lina Wertmuller’s “The Seduction Of Mimi,” called “Which Way Is Up,” converting the eternal schlubby Mimi of Wertmuller’s film into Leroy, a California grape picker who accidentally becomes a union leader. It is easily one of Pryor’s best performances as he (Pryor) plays several different characters in the same way that he could do onstage, with total commitment and at the drop of a hat.

While “Which Way Is Up” was filming, another successful African-American director from that decade, Melvin Van Peebles, contacted Pryor. Melvin wanted to make a biopic about Wendell Scott, a World War Two veteran, moonshine runner, and a stock car racer on the Dixie Circuit who would become the first African-American to drive for NASCAR. With another opportunity to play the lead, Pryor was onboard for the project, and the film would be fittingly titled, “Greased Lightning.” Unfortunately, somewhere during the casting process, Van Peebles and the producers of “Greased Lightning” began to have artistic differences, and Van Peebles was dismissed, leaving the film without a director. Eager to play Scott, Pryor asked Schultz while making “Which Was Is Up” to helm the project, and Schultz agreed. Shortly after the wrap of “Which Way Is Up,” Schultz and Pryor began work on “Greased Lightning.”

A lot of talent was attached to “Greased Lightning.” Besides Pryor, the absolutely gorgeous and talented Pam Grier was selected to play Scott’s wife, Mary, and she turns in the best performance of the pic. Cleavon Little (Sheriff Bart from the Pryor scripted Blazing Saddles) as Scott’s best friend, Peewee. Beau Bridges as Hutch, Scott’s only white friend and mechanic, and famed folks singer Richie Havens as would play Scott’s other mechanic, Woodrow and also contribute more than a few songs for the soundtrack, songs that at times supply the Greek Chorus for the film. Sadly even with all of that talent, it becomes clear as to what the artistic differences must’ve been between Van Peebles and the producers as this feels like quite the hatchet job.

First off, the tone of the film is almost unbearably light, like that of “The Buddy Holly Story,” which considering the amount of racism inherent in Wendell Scott’s story, some pretty awful moments of real hate from Scott’s life play out almost as comedy, and I would imagine Van Peebles would never even think of shooting it that way. What is truly unbelievable about the mellowing of those moments is that during the filming of “Greased Lightning,” racially biased locals in Georgia did everything they could to louse up the production, including whistling and yelling whenever director Schultz would yell “action.” Things got so bad in fact that Schultz would have to substitute the words “action” for “cut” so that the antagonizing yokels would be confused as to when to start yelling. Also the producer’s “feel good movie” intentions are made even clearer as “Greased Lightning” was released with a “PG” rating, which almost guarantees that any edge of that pesky racism would be almost entirely removed without expletives that would naturally be attached to such hateful speech.

Secondary to the watering down of Wendell Scott’s story is the editing which stunts almost every moment of real emotion from carrying through to the viewer. As stated earlier, Pam Grier puts a ton of love into her performance as Scott’s wife Mary, she carries so much love and hurt on her face, but most of her scenes are quickly cut before they can impact you. Beau Bridges’ gives a fine performance and is comedically great as Hutch, who first mocks but then befriends Wendell. Their scenes together are quite good, but, again, they are sliced down to almost nothing by the middle of film, so we never see the relationship mature in any logical way. Cleavon Little is relegated to just quick comedic insertions during most of his scenes, which is a waste for such a talented actor. The few racing scenes are well shot and are very exciting, especially Scott’s first race where he goes over the wall and comes back to finish the race, but those scenes are few and far between. The greatest editing sin is that shortly after Scott finally begins to win a race, the film cuts to him as an aging and medically challenged retiree at the age 42! The jump is stupefying as we have little idea of where his friends and crew have been during this time, and it makes his eventual win at the Grand Nationals, which ends the film, anticlimactic.

Original 1977 Trailer for Greased Lightning

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTlM__C5AbE

It feels like there is more of a film there somewhere as “Greased Lightning” isn’t sure whether it wants to concentrate on Scott the driver, Scott the husband, or Scott the friend, and the film does none of these aspects of this heroic man any real justice. Richard Pryor does as well with the material as he can and proves that he can perform drama almost as well as comedy, and only one year later in 1978, Pryor would stun critics with his fine dramatic performance in director Paul Schrader’s best film, “Blue Collar.” Sadly, Michael Schultz, who continues to direct television to this day, in that same year of 1978, directed Peter Frampton and The Bee Gees in a musical interpretation of the Beatles, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band,” a film so horribly misconceived and painfully executed that it makes you wonder if Schultz was so rattled by the poor box office and criticism of “Greased Lightning” that his instincts were completely off for the remainder of the decade.